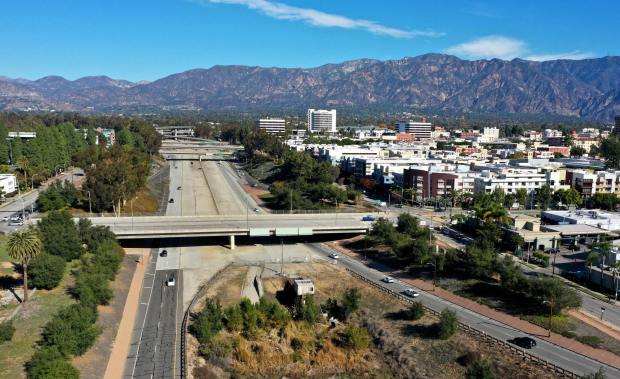

An overhead view of the 710 Stub in Pasadena. (City of Pasadena)

Contrary to an initial belief that property owners were forcibly displaced by the state government using eminent domain, a majority of those affected by the I-710 extension in Pasadena actually consented to selling their homes to the government amid uncertainties about the project.

That is according to Elysha Paluszek with Architectural Resources Group, a consultant hired by the city to gather historical data on the people and buildings displaced by the now defunct 710 freeway extension nearly six decades ago.

“Our research indicated thus far that properties were obtained using a process called hardship acquisition rather than eminent domain,” Paluszek told Pasadena’s Reconnecting Communities 710 Advisory Group during a meeting on Wednesday, April 17.

“Hardship acquisition is used when there is uncertainty about the outcome or timeline of a project,” she added. “Property owners can request hardship relief from the state in advance of a project moving forward. This occurred due to the uncertainty surrounding the 710 and its route.”

Paluszek’s research is part of a broader effort by Pasadena to produce a historical accounting of the effects of the failed 710 North freeway expansion project.

During the 1960s, the California Highway Commission devised plans to route the last five miles of the 710 freeway through parts of El Sereno, South Pasadena, and Pasadena, directly impacting thousands of residents and their homes.

In Pasadena specifically, this decision entailed cutting through the city’s Black and low-income neighborhoods in the northwest, a move that recent academic research has revealed has had a lingering impact. As a result, at least 4,000 residents were displaced, and 1,500 homes were demolished.

Previous narratives have suggested that the state government cleared the construction using eminent domain, a constitutional power that allows the government to seize private properties for public use.

Up until Wednesday, the city’s effort has largely focused on how eminent domain played a role in the displacement of the mostly minority and low- income residents in the neighborhood to make way for the freeway expansion. In its request for proposal for this project, for example, the city noted that the consultant will be tasked with documenting “the eminent domain process and any available information/documentation related to that process for the SR 710 project.”

This is different from what Paluszek has discovered in her research. As opposed to eminent domain, which involves compulsory acquisition by the government even if the property owner does not wish to sell, hardship acquisition requires the property owner’s consent.

Paluszek’s finding surprise many, but also prompted disagreement over their implications.

Christopher Sutton, an attorney with decades invested in representing tenants in occupied Caltrans homes acquired by the state ahead of the planned freeway, disputed the historian’s findings. In essence, he said, folks didn’t have much of a choice to give up their properties to make way for the freeway, even under the hardship provision.

A lot of the homes were acquired in the 1960s, well before the reform laws of the 1970s allowed for fairer procedures and greater compensation, he said.

“Most of these acquisitions occurred during the time period when no. 1, the courts presumed the taking was valid and you had no right to object; and no. 2, tenants, and even the property owners, received no moving expenses; and number three, small businesses did not receive any goodwill,” said Sutton, who also attended Wednesday’s meeting.

In the early 1970s, a federal court injunction was issued, which stopped the acquisition of the homes unless the property owners requested the acquisition based on hardship. But until then, homeowners felt it was too hard to fight the government and they “essentially gave up,” he said.

“It was a fairly unfair process, and you did not really have a right to object,” Sutton added. “And people did not really feel like they could contest what the government was doing, and so most people would receive this (eminent domain) letter, and they would just give up. It wasn’t like they were voluntarily asking to be purchased.”

Technically, either way, it ends in a negotiation, said Richard McDonald, a lawyer who specializes in land-use and real estate laws at Stoner Carlson, LLP.

“Eminent domain is where the government comes in and says, we want to buy your property to build this freeway…so it has the authority to do that and then it compensates people at the fair market value of the property,” McDonald said. “Hardship acquisition is where the property owner asks the government to buy their property at the fair market value.”

“But the other thing that most people, I think, in this whole debate forget,” he added, “is whether you’re talking about eminent domain or hardship acquisition, the ultimate amount paid tends to be a negotiated amount.”

The findings came as a surprise to many of those on the task force. Advisory Group member Cynthia Kurtz suggested the consultant provide documentation to clarify the difference between hardship acquisition and eminent domain.

“Maybe it’s more my interest than it is the need to know, but I have never heard of hardship acquisition before,” she said. “And I’d like to know, the state choosing it when the project isn’t going forward as quickly as maybe eminent domain when something is about to be done, but what’s the difference to the person who owns the property?”

Tina Williams, another group member, said it’s unclear to her why property owners opted for hardship acquisition at the time.

“Were they doing this out of fear that they wouldn’t get a proper price,” she asked. “I mean, I want to understand the dynamic and the details versus just a, I put in for hardship, so therefore, my property was given this much value and I moved on. Was I forced? Was I influenced? What was going on that made folks do this?”

The city, for its part, said that Wednesday night’s update focused on early research findings. The city does not hold a specific viewpoint on this process “other than it is allowed by state law for transportation projects,” said Lisa Derderian, spokesperson for the city of Pasadena.

“The focus of all the historic work being done is to learn about what took place, how it took place, and the various impacts related to displacement,” she said. “Once we have draft reports, we expect to learn more about all the various impacts of displacement, and hardship acquisition will be one aspect.”

Derderian also noted that Paluszek “shared some broad facts about the process, but did not go into detail,” despite the committee’s efforts to inquire further.

City staffers and the consultant intend to address additional details about the process with the committee in follow-up discussions, she added.

According to Pauluszek, she conducted primary and secondary research using books, journals and newspaper articles. However, she did note that there are no records kept by the state about the properties purchased via hardship acquisition for the 710 freeway project.

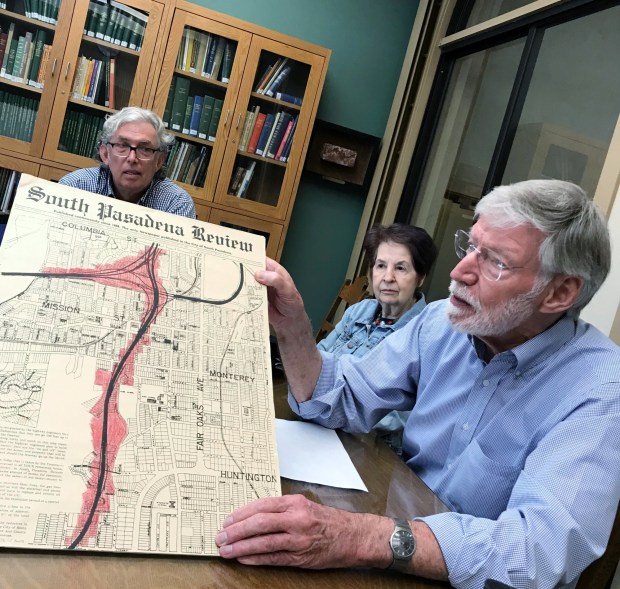

Therefore, the researcher had to obtain that information “as much as possible” through other means, such as city directories, sanborn maps, Caltrans right-of-way maps, as well as newspaper articles, she said.

The findings tap into a re-examination of how freeway construction decades ago in the nation’s growing suburbs and cities split communities and devalued property wealth, often in communities of color.

A 2022 study by researchers from UCLA’s Institute of Transportation Studies examined the impact of freeway construction on such communities. Their report indicated that the 210 freeway, situated north of I-710, primarily passed through African-American neighborhoods, resulting in the displacement of thousands of families.

The UCLA experts will expand their research to include the 710-freeway project as they have also been tasked with studying the impact of freeway construction on segregation in Pasadena, as part of this project.

The city has hired three different historians to study three different aspects of the history of the area for its effort to record the impacts of the 710 freeway expansion.

In addition to UCLA and Architectural Resources Group, the city has also contracted Allegra Consulting Inc., to prepare an oral history on the impacts of the 710 freeway “stub” that was officially nixed a few years ago following decades of community opposition in the east San Gabriel Valley.