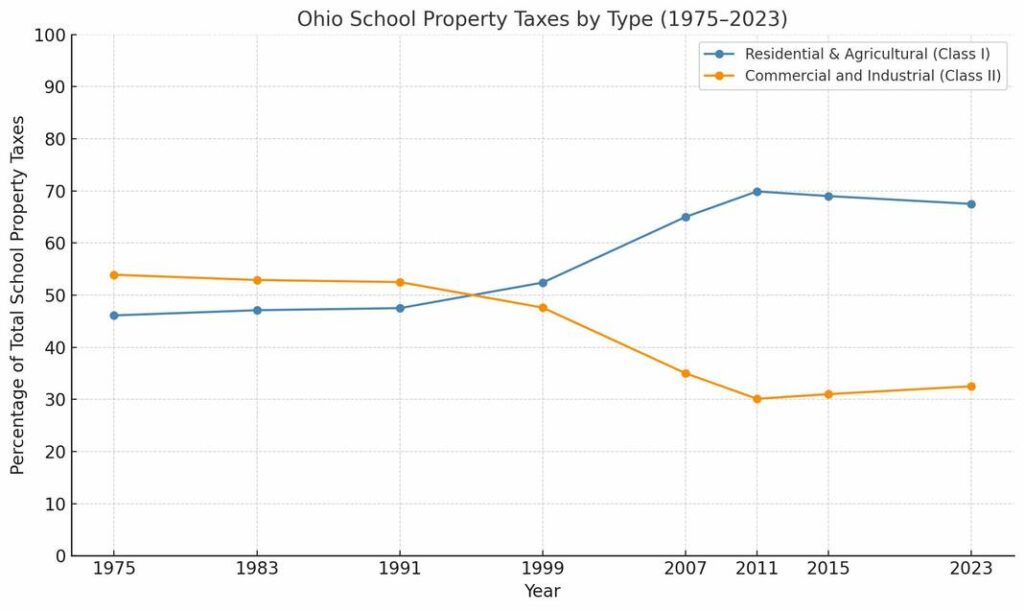

Since 1991, the share of school property taxes paid by residential and agricultural property owners has climbed, while the share from commercial and industrial property has declined. (Source: Ohio Education Policy Institute.)

COLUMBUS — In the winter of 1968, Youngstown’s public schools shut down for weeks.

After multiple levy failures and no emergency aid from the state, the district had $6,000 to cover more than $1 million in payroll.

Teachers went unpaid. Students stayed home. Classrooms didn’t reopen until January, when new tax dollars came in.

“Many didn’t believe we needed the money,” Superintendent Woodrow Zinser told the Akron Beacon Journal that November. “They wanted us to pinch pennies and make do with what we had—just like they did.”

It was, as Zinser put it, a clash between rising prices and diminished incomes.

Fifty-seven years later, that tension is simmering again. Homeowners are frustrated that increasing property values have caused tax bills to spike. State legislators and Gov. Mike DeWine have said they want to grant relief, but some proposals have stirred fears about revenue cuts to school districts and local governments — after years of the state cutting supports.

History, it seems, could be repeating itself.

Another Youngstown?

Youngstown’s closure made national news. It was one of Ohio’s largest school districts — 28,000 students, 47 buildings — and its collapse became a symbol of a system in distress.

Gov. John Gilligan campaigned on the crisis in 1970, calling for a state income tax to ease the burden on homeowners and stabilize school funding.

Lawmakers passed it in 1971. Five years later, House Bill 920 limited property tax increases as home values rose.

“With the passage of the state income tax, people thought there would be enough money and we wouldn’t need increases in real property taxes,” Rep. John Johnson, HB 920’s sponsor, said at the time.

The two policies were meant to balance each other: income taxes to fund services, and limits to protect property owners.

But today, that formula is breaking down at the same time economic factors are colliding.

Inflation has jumped 27% since 2018, and incomes haven’t kept pace.

Teachers say they’re underpaid. Districts keep returning to the ballot. And homeowners across Ohio are facing the steepest property tax increases in a generation.

“Incredible, and a bit depressing, how history is repeating itself,” said House Minority Leader Dani Isaacsohn, a Cincinnati Democrat.

Ohio Republicans passed a flat income tax as part of the 2025 budget and have a long-term goal of phasing it out entirely.

That change comes on the heels of earlier moves to cut business taxes and scale back state reimbursements to local governments.

The result? Local governments, especially schools, are leaning harder on residential property taxes to fund the same services.

In fiscal year 1999, the state covered 47% of the base cost of education, according to the Ohio Education Policy Institute.

This fiscal year, that number dropped to 38%, and it’s projected to fall to 32% by 2027.

That decline isn’t the result of one big cut. Instead, it reflects a mix of frozen funding formulas, outdated cost estimates, and rising property values.

As a result, more responsibility for funding local schools has shifted to homeowners through property taxes.

Democrats and education advocates say this leaves school districts chasing new levies just to keep up with rising costs.

But Republicans argue that schools also need to take a hard look at how they spend money—especially on administrative expenses.

“Ohio has the greatest number of taxing jurisdictions in the country,” said Rep. Bill Roemer, a Republican from Richfield. “We need to look at shared services. We need to look at consolidation. We need to look at ways to deliver services as effectively as possible.”

The slow retreat

Debates about local spending often center on school buildings or administrative costs. But they’ve unfolded alongside decades of policy shifts at the state level.

“For forty years, state government has removed revenue streams from local government,” said Chris Galloway, Lake County Auditor and a member of the governor’s property tax working group. “Not to pass judgment on any one piece of policy, but it adds up.”

Under Gov. John Kasich, the 2012–13 state budget cut the local government fund in half, ended the estate tax, and sped up the phase-out of reimbursements tied to business taxes that had been eliminated in years prior.

According to Policy Matters Ohio, local governments now receive about $1.4 billion less per year — adjusted for inflation — than they did before those changes.

Library funding also took a hit. Forty years ago, no public library in Ohio relied on a property tax levy. Today, most do.

“You compound that across industries for the last 40 years, that’s why we are here right now today,” Galloway said.

Shifting demographics have also added to local pressure.

Youngstown now enrolls fewer than 5,000 students. Cleveland has less than half the population it did at its peak. And while Columbus continues to grow overall, families with school-age children are increasingly settling in neighboring cities.

“There’s a disconnect,” Buckeye Institute fellow Greg Lawson said. “Voters are upset about their property taxes, but we’re not right-sizing things in response to shifting demographics.”

In 2024, Columbus City Schools scaled back plans to close several buildings after strong public pushback.

That reluctance extends beyond school districts. Communities resist efforts to combine services, close buildings, or merge jurisdictions — even when population declines suggest it’s the more sustainable option.

“The right policy is consolidation,” Lawson said. “If you don’t include that, you’re not really being serious. We’ve got to use this as an opportunity to restructure how Ohio’s local governments operate.”

School funding shift

The largest slice of most Ohioans’ property tax bills goes to public schools—often 60% or more.

“If you want to solve the property tax situation in Ohio, there is no way to do it without addressing school funding,” Galloway said. “None.”

School advocates say one major reason your property tax bill has gone up is the elimination of certain business taxes.

For years, Ohio taxed business equipment and machinery through the tangible personal property tax. But lawmakers phased it out between 2005 and 2009.

“That particular tax hurt Ohio,” said William Shkurti, a Democrat and former state budget director. “Guess who holds a lot of tangible personal property? Manufacturing.”

But the change “put less taxes on businesses and more on people.”

Today, Ohio homeowners pay more than two-thirds of all property taxes — and that share could keep growing.

A new law taking effect in August, House Bill 15, cuts property taxes for power plants that expand or upgrade their equipment.

“Communities that have power plants are going to get gutted,” Galloway said.

He pointed to Perry Nuclear Power Plant, which pays a 25% tax rate on current equipment. Under the new law, new equipment will be taxed at 7%.

“We carved out (an exemption) because we believe we’ve got to have more energy generation. We do. It’s an admirable goal,” Galloway said. “But there was absolutely no reason to change the tax structure.”

At the same time, lawmakers have kept the non-business credit, which gives a 10% property tax break to residential and agricultural owners.

Critics say that sounds good, but large rental companies shouldn’t be getting it.

Sen. Bill Blessing, a Cincinnati Republican, wants to limit the credit to owner-occupied homes and use those dollars to increase the homestead exemption for seniors and low-income residents.

Ohio is also below the national average for school funding, according to analysis by the non-partisan Legislative Budget Commission.

The national average in fiscal year 2023 was $8,971 per pupil.Ohio spent $6,647 per pupil.

On the other hand, Indiana sent its schools $9,212 per pupil that year. In return, LSC wrote that its homeowners paid $700 less in property taxes.

Conservatives say Ohio taxpayers deserve a closer look at how school dollars are spent.

According to a 2022 Brookings Institution report, Ohio spent 49% more on district administration than the national average.

The state ranked 47th in education spending going into classrooms, but ninth in money spent on administration.

End of income taxes

Ohio’s income tax has been shrinking for the past decade, dropping from nine brackets to a single flat rate in the most recent state budget.

Republicans argue that eliminating the income tax will make Ohio more competitive.

Sen. George Lang, a Hamilton County Republican, called the tax one of the worst economic decisions Ohio has ever made.

“We went from one of the most business-friendly states in America to one of the least,” he said when the state budget passed in June.

He blamed the income tax for the state’s loss of congressional seats and said repealing it would turn things around.

Others see the shift differently.

Local governments say they’ve borne the brunt — not through smaller state services, but through cuts to their funding.

“It appears, in this last budget, the priorities of the state were to give tax reductions to wealthy people, money to the owners of the Cleveland Browns, and to support religious schools,” Shkurti said.

Simmering anger

Fixing Ohio’s tax system has never been easy.

Property taxes in Ohio have become a Gordian Knot — an impossibly tangled system, pulled tighter by state cutbacks, local tax breaks, and a constitutional formula few can explain but everyone feels in their bills.

No one has managed to untie the knot. Now, a group of frustrated homeowners wants to cut it.

Sara Wolf is one of them. The Cincinnati-area resident is gathering signatures for a constitutional amendment that would abolish property taxes entirely. No more levies. No more rollbacks. No more millage math. Just a clean break.

“We didn’t come up with our petition from nowhere,” Wolf said. “We have been trying just for the last two years to have them look at that abomination of an assessment.”

Her own home was reassessed in 2023, and the value jumped from $215,000 to $700,000. Her property taxes went up by $10,000.

Wolf appealed the change, spending months navigating the system. She eventually won a reduction to $410,000 — but the process left her shaken.

“There is no relationship between what your house is worth and what the government needs to operate,” she said.

For Wolf and others, the fight has become about more than taxes. It’s about freedom, fairness, and the feeling that the system no longer works for the people living within it.

She knows an 85-year-old woman who’s looking for work to pay the taxes on a home she’s lived in for 50 years.

“We can’t live like this,” Wolf said.

DeWine vetoed several relief proposals in the state budget, including capping how much money school districts could keep in reserve, eliminating emergency and replacement levies and changing how the “20-mill floor” is calculated, a key formula that affects how much property tax schools collect as home values rise.

He said then his fear was that imposing them all at once on local schools would create a “huge, huge problem.” He then appointed a panel to come up with recommendations.

Blessing, Galloway, the County Auditors Association of Ohio, and even Republican House Speaker Matt Huffman have warned that ending property taxes outright, as Wolf’s amendment would do, could be chaotic, even catastrophic.

But Wolf doesn’t see any other way to get their attention.

“Our governor would not even meet with homeowners, and now he has a task force,” she said. “Now their ears are perked up.”

One thing is clear: If voters cut the Gordian Knot and ban property taxes, Ohio will have to rebuild its entire system for funding local governments — from the ground up.