In Epsom, one resident panics. In Hopkinton, another has sympathy for seniors. In Pembroke, people cringe. In Weare, there’s disappointment for the lack of state funding. And in Henniker there’s appreciation that the school and select boards tried to balance budgets as best they could.

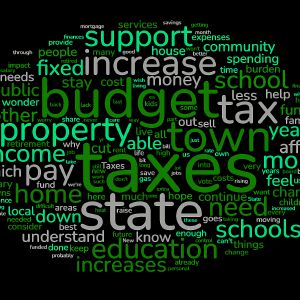

Throughout Merrimack County, Monitor reporters posed a question to residents at Town Meetings and deliberative sessions. The prompt was simple, “When my property taxes change, I…”

Each year, Town Meeting offers a window into the fabric of each town. Our answers did, too.

We heard from residents who are adjusting their personal budgets to keep up with tax increases. That means cutting discretionary spending from Dunkin’ orders to charitable donates. For others, it means cutting back on more essential spending, like gas, groceries and home heating oil in the winters.

Landlords lamented they had to raise rent. Renters felt the brunt of this burden.

We also heard from voters who directed their frustration to state leaders in Concord. School funding was a repeated concern, with gripes for the state to “pay its fair share of expenses” for public education.

Elected officials in their town — on school and select boards — were keeping costs down as best they could with the cards they were dealt, they said.

Then there were the residents who were reconsidering stay in town.

A homeowner in Hopkinton said they consider selling their house and moving. A long-time Warner resident questioned if they could continue to live in their “forever home.”

The Monitor collected 132 answers from residents in 20 towns. Among the varied responses, one message was clear: People had something to say.

Catharine Matteo has been holding off on buying a new car for a decade. Her current ride is 22 years old with 250,000 miles on it.

It keeps rolling along,but just barely, she said.

“I am in no shape to go and get another vehicle. I cannot take on a car loan,” Matteo said after the Hopkinton school district meeting, where her taxes increased yet again. “I just keep putting it off every year. I’m hoping this one doesn’t die”

With taxes climbing steadily, Matteo, who has lived in Hopkinton for seven years, feels it’s time to make some tough choices — not just about her car, but about her day-to-day life.

To save on oil, she is forced to keep her house in the low 60s this winter. She’s considering letting go of her neighbor who plows her driveway because she can no longer afford to pay him. She’s also planning to raise the rent on the upstairs unit she rents out.

Matteo warned that if this continues, Hopkinton will drive away all its long-time residents.

“Eventually this town is going to be nothing, but either, dirt poor that has some kind of state assistance that can keep them here in other ways, which is also taxpayer-funded, or the uber wealthy that are nothing but happy blank checks,” said Matteo.

This year, Hopkinton’s school district approved an operating budget of $27.4 million, and Matteo can’t seem to wrap her head around why a district with around 955 students would need such a large budget.

With the new tax rate, Matteo said she would need to set aside around $2,000 a month to pay her property taxes.

As taxes rise, even when it’s to support public education, Matteo said it gradually impacts families, with parents struggling to afford things like piano lessons or tutoring for their children.

“The same people show up every year to speak out about being more transparent, being more lean, being more conscientious with other people’s money, the taxpayers money,” said Matteo. “But at the end of the day, actions speak louder than words, and we’ve never seen a decrease in at least the seven years we’ve been here. It is not sustainable.”

Donna Keeley, a longtime Republican, decided to permanently un-enroll from the political party last week when she went to vote in her town and school elections.

“That was really just a message to the Republican party,” she said in an interview. “Sayonara!”

Keeley, 62, said that as the school portion of her property taxes has risen over the years, her frustration has turned not to the school district itself, but rather to her state representatives.

“We have two state reps who do not support our public school system,” Keeley said. “They support the [Education Freedom Account] system, but they do not speak to their constituents about how it’s going to impact the local property tax rate as it relates to the school.”

Keeley never had children of her own and is retired from a career working in community relations at a utility company, but she has always felt a responsibility to fund her public schools.

“When you live in a civilized society, this is one of the things you pay for,” she said.

For Keeley and for her neighbors that has grown increasingly difficult. Pittsfield, a low-income town, has one of the highest tax rates in the state, according to the Department of Revenue.

Last week, voters — some of whom are saddled by property tax bills they simply cannot afford — approved an operating budget that will force the district to make cuts.

Keeley has followed the funding debates that have played out in New Hampshire for the last three decades. She sees the wealth of resources available to her three nieces who teach in Meredith where, because of high property values, the tax rate is among the lowest in the state — a full $20 per $1,000 of property value below Pittsfield’s.

“The state needs to figure out how they can make it work so that it isn’t a burden on every single town in terms of the taxes that they pay,” Keeley said. “And right now it’s not fair and equitable.”

Mary Watts envisioned a family homestead.

At the turn of the century she and her husband moved to Warner. They bought a piece of land and put every last dollar into it, building a three-bedroom, two-bathroom house she hoped her children would inherit.

That’s still the dream, per se. But each year it seems a bit further out of reach.

The need for a new roof now counters desires to “retire on time.” And while Watts, 63, hopes her daughter, who lives in Manchester, will boomerang back to Warner like many residents do, she also fears she’ll be in the same predicament.

“Will our children be able to afford the taxes on what we’ve built?” said Watts. “Because every time you improve something, the taxes go up.”

To Watts, concerns over rising taxes have built year after year since she’s moved to Warner. She likes to think of the town as frugal — putting money away each year for costs down the road

School spending recently has not followed the same approach, she said.

“It just feels like everything is out of control and unsustainable,” she said. “Something has got to give somehow.”

Last year, Warner residents welcomed a year of reprieve with the local tax rate — a one-time windfall from the sale of a local cell tower meant the town portion of property tax bills was $9.15. The school portion was nearly double that, at $17.31.

“I don’t have any solutions,” she said. “I wish I did.”

Still, the town has one of the highest tax rates in the state and last week residents approved a budget that will increase the local tax rate by 29 percent.

Watts was in the audience for the budget vote and first few warrants. At a certain point, she and her husband headed out early. She had work in the morning in Manchester.

“We have day jobs,” she said. “You just can’t give up that much of your time to, even though it’s important, to sit there and wait until midnight to finally get that last vote.”

Bill Kuch has lived all over the world.

A former general manager for the Digital Equipment Corporation, he bounced around from Switzerland to China, Thailand and Singapore for 20 years before returning to New Hampshire. Every move is a disaster, he explained, especially after you reach a certain age. Movers break fragile items, and some “junk” always gets lost in transit.

Kuch, a 78-year-old retiree living in Bow, said he loves the town and doesn’t want to move again — but he seriously considers the possibility whenever his property taxes increase.

“Parents come here because they want a good education for their kids, and I accept that. As soon as they graduate, they’ll leave town, but while they’re here they’ll vote for anything the school board proposes. I can see the benefit, but it doesn’t help me out,” he said.

Kuch estimates his property taxes “suck up” one-third of his Social Security benefits. He and his wife don’t rely exclusively on SSA checks for their retirement, and they live on a fixed income he described as “pretty decent.”

Still, Kuch, who during two terms represented district Merrimack 23 as a Republican in the New Hampshire legislature, said he feels an urgency to act to prevent future property tax increases.

He no longer identifies with the party — instead, he calls himself a conservative independent — he does advocate for any solutions that push schools to “cut the fat.” For instance, he suggested that pivoting to an SB2 form of self-government would free older Bow residents, who may not have the stamina to sit through long town meetings, to more easily address budget bloat directly on the ballot.

“What I will do is vote against anyone who wants to raise property taxes,” he said. “With that and SB2, I guarantee you the taxes won’t go up as much.”

Reporters Michaela Townfighi, Sruthi Gopalakrishnan, Jeremy Margolis and Rebeca Pereira developed this report.