See which national real-estate firms own 7,000 central Ohio rental homes

A handful of national landlords have acquired thousands of central Ohio rental homes, raising concerns about their impact on neighborhoods.

- A handful of national real-estate firms have bought nearly 7,000 central Ohio homes to rent out.

- Many of the homes are in the fringes of Columbus or in suburbs.

- Companies say the homes provide an important alternative to traditional rentals but critics say the move pushes out buyers.

A handful of national landlords have acquired thousands of central Ohio rental homes, raising concerns about their impact on neighborhoods and central Ohio housing costs.

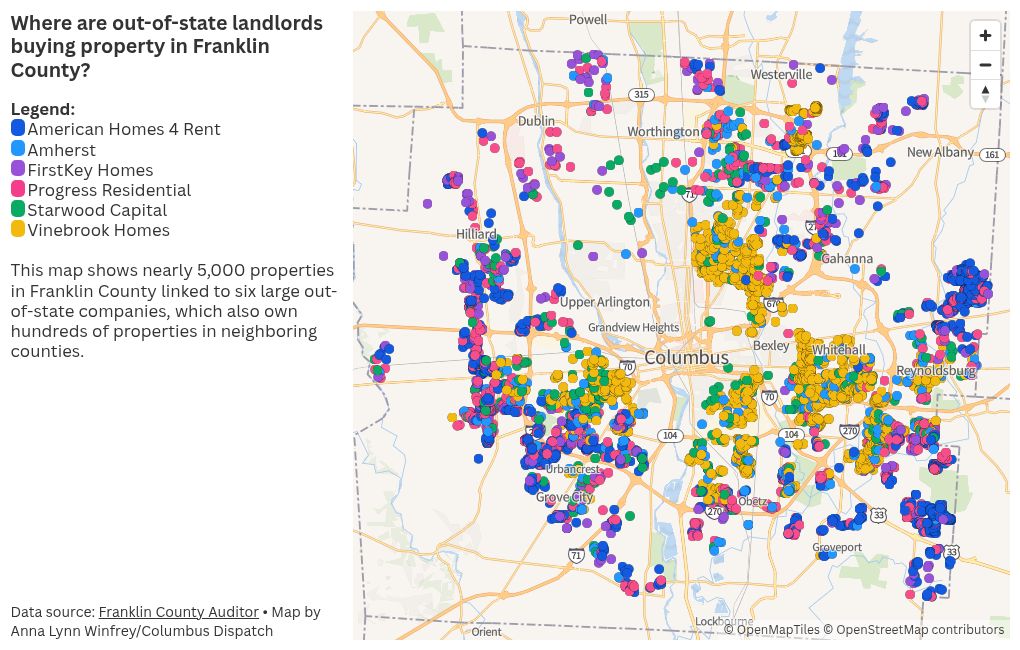

A Dispatch analysis of Franklin County property records shows that six national companies each own more than 400 properties in the county. Together, the six landlords control more than 6,000 Columbus-area homes.

The two largest institutional owners of central Ohio rentals, American Homes 4 Rent and Vinebrook Homes, which each own more than 1,600 Columbus-area homes, have been active in central Ohio for more than a decade.

Starting around the time of COVID, four other major national players entered the Columbus market: Pretium Partners, whose properties are managed by a sister company, Progress Residential; FirstKey Homes; Starwood; and Amherst, which manages its homes through Main Street Renewal. Several smaller out-of-state firms have also entered the Columbus market in recent years including Brick & Vine and Whitestone Companies.

Unlike some earlier corporate investors, who acquired many of their homes from inner-city foreclosures, most of the new landlords are targeting nicer homes on the edge of Columbus in adjacent school districts, in places such as Grove City, Canal Winchester, Obetz, Blacklick, Reynoldsburg, Minerva Park, Groveport, Galloway, Gahanna, Pickerington and into neighboring counties.

Critics say the companies push up home prices, make it harder for buyers to find homes, and drag down neighborhoods by replacing owner-occupants who care about the home with indifferent corporate landlords.

“We do have concerns; the biggest is the effect on prices,” said Carlie Boos, executive director of The Affordable Housing Alliance of Central Ohio. “They are raising prices across the board.”

Some studies suggest that corporate investors are also associated with higher rents, but others note that the investment firms are also more likely to own nicer homes in nicer neighborhoods, which would naturally command higher rents.

The companies and those who have studied the industry note that corporate owners own a tiny fraction of all homes, including rental properties.

They also say the companies provide a valuable service to families who want a standalone home in a nice area but can’t afford to buy, or don’t want to. Institutional investors, they argue, expand opportunities for families to rent in neighborhoods that previously offered few single-family rental homes.

“Single-family home rentals at their essence provide another option in the housing mix,” said David Howard, chief executive officer of the National Rental Home Council, which represents the industry.

“Traditionally, you’ve had two options — ownership and apartments. Now you’re seeing that middle becoming more defined. … The larger providers bring some definition, in terms of professional management and expertise, and provide consumers the option of living in a desirable neighborhood.”

When did corporate landlords start buying Columbus homes?

Corporate ownership of single-family homes in the Columbus area isn’t new.

Long before national players got into the Columbus act, local companies accumulated hundreds of rental homes, concentrated in parts of the inner city and around Ohio State University. Local landlords of single-family homes, some of whom own more than 100 homes, still far outnumber national corporate landlords in Columbus.

But what had traditionally been a mom-and-pop local industry took a turn after the housing recession of 2007 – 2011, when millions of Americans lost their homes to foreclosure. National investment firms started buying the remains in bulk and renting them to tenants who wanted a home but were no longer able to buy one.

In Columbus, institutional investment started on July 10, 2012, when American Homes 4 Rent paid $903,019 for 10 homes that had been foreclosed upon. The following year, a predecessor of VineBrook homes bought 1,900 homes on a single day from the widow of a Dayton-area real-estate developer, marking its entry into the Columbus market.

The most common definition of “institutional investor” is a company that owns at least 1,000 homes in multiple states. According to a 2024 report by the General Accounting Office, no single investor owned more than 1,000 homes in the U.S. at the end of 2011.

But by June 2022, more than 30 investment firms each owned more than 1,000 single-family homes, for a total of 446,000 U.S. homes, or about 3% of all single-family rentals, according to a study by the Urban Institute.

The Urban Institute concluded that Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis are among the top 20 markets in the nation in concentration of large corporate owners of single-family homes. The institute estimated that institutional investors own 6,908 homes in the Columbus area, about 7% of all single-family rental homes.

Columbus and Cincinnati, though, pale in comparison to markets at the top of the list, which are concentrated in the Sunbelt. According to the Urban Institute, 29% of Atlanta’s rental homes are owned by large investment firms, followed by Jacksonville, Florida, with 24%, and Charlotte, North Carolina, with 20%.

Howard said national investors expanded beyond the Sunbelt to places like Columbus to meet demand and growth.

“Columbus has become a vibrant market, with immigration, population growth, companies expanding,” he said. “Those are the kinds of things that drive demand and interest from rental home providers. There’s demand there.”

Amherst CEO and Chairman Sean Dobson said the Texas-based company, which owns about 600 central Ohio homes, was drawn to the market by its economic vibrancy.

“Columbus is a little jewel, it’s growing, it’s got a young population, and it has an older housing stock that can serve the modern population if you invest in it,” he said.

Which Columbus neighborhoods have the most institutional investor landlords?

Despite sweeping concerns about the industry, one size does not fit all large corporate investors.

“Not all institutional investors are the same,” said Kathryn Reynolds, one of the authors of the Urban Institute report.

The two biggest investors in central Ohio illustrate the point.

American Homes 4 Rent’s 2,179 central Ohio homes on average are 1,890 square feet, built in 2003, worth about $206,000, largely sit on the edge of the urban core, and rent for $2,235 a month, according to company reports.

Vinebrook’s 1,621 central Ohio homes, by contrast, are concentrated in Linden, the Hilltop, Blacklick and the East Side and rent for an average of $1,327 a month, an amount that would qualify as affordable housing depending on how many residents occupy the homes.

But Vinebrook’s affordability comes at a cost. The company’s upkeep of its properties has frequently been the target of complaints and lawsuits, including one with with the city of Cincinnati that was eventually dismissed. A Dispatch analysis last year found that Vinebrook was among the top code violators in Columbus from 2019 through early 2024. A smaller institutional investor in Columbus, Denver-based Whitestone & Co., has also been in the news for complaints about its properties.

But as Reynolds notes, there’s no real evidence that institutional investors are better or worse landlords than smaller companies or mom-and-pop owners.

Most of the big new players in the Columbus market hew closer to the American Homes 4 Rent model — newer, pricier homes on the edge of the city or in the suburbs that weren’t home to many rentals before. Subdivisions in Blacklick, Obetz, Reynoldsburg, Galloway and elsewhere that were built from the mid-1990s into the early 2000s are full of homes owned by the investment firms.

The homes offer different neighborhoods, and different prices, from traditional Columbus rentals. Rentals from FirstKey Homes, for example, commonly lease for more than $2,500 a month and even top $3,000 a month, and can be found in Dublin, Lewis Center, Hilliard and Westerville. Property records show that FirstKey paid over $300,000 for some of its homes.

“We want to be where schools are good, neighborhoods are safe, where there’s need,” said Dobson, with Amherst.

What impact do corporate landlords have on neighborhoods?

Several studies have concluded that institutional investment activity tends to raise the value of homes in neighborhoods, though not dramatically.

A study published in 2022 found that sales prices of homes within a quarter mile of bulk home investments increased 1.4% more than homes located farther away, and concluded that institutional investors helped “spur the recovery of distressed housing markets.”

Another study, by Joshua Coven, a PhD student in finance at New York University who is an incoming assistant professor at Baruch College, found that in areas where institutional investors own at least 1% of rental homes, prices rise 2% more than in areas without the investors.

While rising home value is good for homeowners and sellers, it leads to a common concern: that investors price out young and first-time buyers because they pay more, pay in cash and buy in bulk.

“They’ve gobbled up the inventory,” said Boos, with the The Affordable Housing Alliance.

For Coven, institutional investors result in “a tradeoff between owners and renters.” While investors “increased prices for perspective owners,” they also provide opportunities to rent homes in new areas, he found.

“The increase in the supply of rental housing allowed the financially constrained to move into neighborhoods that previously had few rental units,” Coven noted.

Tenants, neighbors react to institutional investors

Tuffey Cochrane and his family moved into a Progress Residential home in the Waggoner Chase neighborhood of Blacklick, in the Licking Heights School District, about four years ago. He wasn’t looking to buy a home in Columbus because he expects to return to the Atlanta area, but he also wanted a home in a nice neighborhood for his family.

“I like the location, like the house,” he said. “There’s enough room for the kids, it’s a good neighborhood with good schools.”

Two doors down, Blake Edstrom cited similar reasons for his family’s move into an American Homes 4 Rent home.

“There’s more room here than where we were and we wanted to stay in Licking Heights schools,” he said.

Next door to Cochrane, Ed Nesser has watched those two homes turn into rentals, along with the one between them, owned by FirstKey.

Nesser gets along fine with the tenants and said the investors appeared to improve the interiors of all three homes when they bought them. But he has concerns about the lawns and landscaping of the homes, which renters are responsible for.

“They did a lot of work in the houses but nothing with the landscaping,” said Nesser, who has lived in the neighborhood 22 years. “We had a family from St. Louis who planted a lot of flowers, but very few renters take pride in the outside of a house.”

Boos sees that as a key problem with investors. As she puts it, “they’re not involved in the neighborhoods.”

Howard, with the National Rental Home Council, says national investors improve the homes they buy and said spend an average of $30,000 on each home they purchase.

David Painter, the director of the Center for Real Estate at the University of Cincinnati, found that while institutional investors tend to improve their homes when they buy them, they do not spend as much money over time on the homes as homeowners or even smaller investors.

“There’s a clear pattern, the owner-occupied homes pull more permits and the permits are likely to be of higher values,” said Painter, who based his findings on data from the Charlotte and Minneapolis areas. “Large landlords are least likely to pull permits for remodeling and when they do, it’s less likely to be large projects.”

Despite his concerns about long-term investment in corporate-owned rentals, Painter sees value in the industry.

“I care about how reinvestment in housing is happening; that’s an important issue,” he said.

“Issues around access also remain important. We want people of lower and moderate income to have more choices of what houses they can occupy. That’s why we want housing choices of all types in different neighborhoods, for those who don’t have money for a down-payment but want the best home possible for their family and kids.”

For Amherst’s Dobson, providing a rental alternative for families is key.

“There are tons of studies that show that where people grow up makes a huge difference in their future,” he said. “What’s lost in the conversation is who we serve.”

Pros and cons

Boos also believes institutional investors are more likely to impose “junk fees” such as lawnmowing charges, on tenants, and points to studies that institutional investors are quicker to evict than local landlords.

Such concerns have led some politicians to propose curbs on investor activity.

Ohio Sen. Bill Blessing, R-Colerain Township, introduced a bill in 2022 that would give other buyers an opportunity to buy foreclosed homes before large investors have a chance.

Large home investment firms have been “devastating to the health of our nation,” Blessing said at the time.

In 2023, then U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, proposed blocking some federal tax breaks for companies that own 50 or more single-family homes.

Defenders argue that rising home values is a good thing, and note that the evidence is mixed on whether institutional investors raise rents in areas. Coven said his research found that institutional investors actually result in rent decreases because they can operate more efficiently than smaller local investors and because they increase supply and competition among landlords.

“Policies seeking to ban institutional investors or cap annual rent increases would increase rents by reducing the rental supply — the opposite of their intended effect on the rental market,” he concluded.

In addition, some studies have shown that most renters of single-family homes would not be able to afford to buy homes, especially in the neighborhoods where they rent.

Amherst, for example, estimates that about 85% of its tenants would not qualify for a mortgage on the home they rent because of their credit history, lack of down payment and income.

Is investor activity slowing?

New institutional investors bought most of their Columbus properties from 2019 through 2022, but buying has dramatically slowed the past two years, suggesting that the industry is heading in a new direction.

According to the real-estate company Redfin, investor activity peaked in 2021 and 2022, when investors (institutional and otherwise) acquired about 6,000 Columbus-area homes each year, one out of every five or six homes sold. In 2023, that dropped to 3,771 homes and last year it fell to 3,500 homes.

Some big investors have even started selling their Columbus homes. Vinebrook, for example, sold 24 Columbus homes last year, along with 200 Cincinnati homes.

Investors who remain active in central Ohio are largely smaller local ones looking for urban bargains, said one real-estate agent who helps investors find Columbus homes.

“The buying from an institutional perspective is down 90% from what it used to be a few years ago,” said the agent, who asked not to be named. “The market has definitely slowed and the quality of buyer has changed.”

The median sales price of a central Ohio home rose from $210,000 in 2019, when corporate landlords began expanding in central Ohio, to $320,000 last year, a 52% jump. Those prices, coupled with elevated mortgage rates, have kept demand high for single-family rentals.

The housing industry is targeting that demand with a rental-home twist that has landed in central Ohio: building homes to rent, not to sell. Last year, 39,000 build-to-rent homes were constructed in the U.S. including 1,018 in central Ohio, the sixth-highest number in the country, according to Point2Homes, a listing service that tracks the industry.

Even some institutional investors are shifting toward a build-to-rent model. American Homes 4 Rent has started building homes to rent, including Eastwood subdivision on Henley Road in Reynoldsburg and others proposed or underway in central Ohio, along with Pretium Partners, a sister company to Progress Residential.

“You’ve seen a pretty significant drop-off of homes being purchased by companies,” said Howard. “There are just fewer opportunities for companies to purchase homes, less inventory and the cost of capital is high. …

“Companies are still growing by building new homes,” he added. “I think we’re going to continue to see an emphasis on building; build-to-rent will play a larger role in the industry.”

Either way, with home prices and mortgage rates elevated, there’s no sign that demand for single-family rental homes will slow any time soon.

Dispatch reporter Anna Lynn Winfrey contributed to this report.

Real estate and Development Reporter Jim Weiker can be reached at jweiker@dispatch.com and at 614-284-3697. Follow him @JimWeiker