Exchange-traded funds have evolved a lot over the past three decades, and they introduced a lot of investor-friendly innovations along the way. But those great innovations came with a cost: an ocean of expensive and speculative ETFs that investors should ignore.

ETF providers, or the asset-management firms that create and manage ETFs, aren’t charities. At the very least they have to earn a living, so they expect to make a profit off the ETFs they provide. Profit is a powerful motivator. It can encourage genuinely great developments or it can promote speculative strategies that take advantage of investors.

ETFs have seen their share of both. A lot of great ETFs have come into the world, and more will likely appear. But there’s a growing number that are questionable—if not downright dangerous. They prioritize providers’ interests above investors’. A quick look at where ETFs came from, how they grew, and the incentives behind their development explains the dearth of speculative ETFs roaming exchanges.

Humble Beginnings

The motivation to create the first ETF came from the need to revive some of the smaller US exchanges. The American Stock Exchange and Philadelphia Stock Exchange had fallen from prominence by the late 1980s. Traders had migrated to the younger Nasdaq, which opened its doors in February 1971, and their bigger brother: the New York Stock Exchange. Some creative minds thought that a novel new instrument could spark more trading volume and save these dying exchanges.

Nate Most, head of product development for the American Stock Exchange, had the idea to mimic a warehouse receipt—a tradable instrument representing ownership in a commodity that was stored in a warehouse. Traders could buy and sell the receipts to transfer ownership without the need to physically move bushels of corn or bags of cocoa. His vision extended that idea to S&P 500 stocks, which could be “warehoused” in an account, while shares representing an ownership stake in the portfolio traded on an exchange.

The first true ETF started trading on the Toronto Stock Exchange in March 1990. US exchanges made subsequent attempts. Few got past regulators, and those that passed were tough to sell. State Street and the American Stock Exchange finally got the green light in early 1993 after years of back and forth with the SEC. SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust SPY started trading in late January, and it has grown into one of the largest ETFs today.

An Insatiable Appetite

More ETFs came on line in the following years as their popularity increased. State Street created its second ETF, SPDR S&P MIDCAP 400 ETF Trust MDY, in May 1995. Then, iShares launched a slew of ETFs tracking markets from abroad. Almost 100 ETFs traded on US exchanges by the start of the new millennium.

The early success had certainly increased trading volume, but the ETF business was no longer about saving smaller exchanges. Mutual funds were changing in ways that played into the hands of ETFs. The long-term merits of low-cost index funds had taken hold, and they easily slotted into the ETF’s index tracking framework.

Investors would slowly realize that ETFs had a big advantage over their mutual fund counterparts. The in-kind transactions that allow ETF shares to tightly track the value of their underlying portfolios were tax-free. Asset managers that could effectively manage those transactions could easily contain, if not eliminate, taxable capital gains. Tax-free in-kind transactions tipped the scales to favor ETFs. They were arguably one of the most important financial innovations for modern investors.

Broad-market indexes and slices of those indexes, like individual sectors and countries, dominated ETFs by the early 2000s. Vanguard launched its first ETF in May 2001: a share class of the popular Vanguard Total Stock Market Index VTSAX. It would eventually tack an ETF share class onto nearly all of its index-tracking mutual funds.

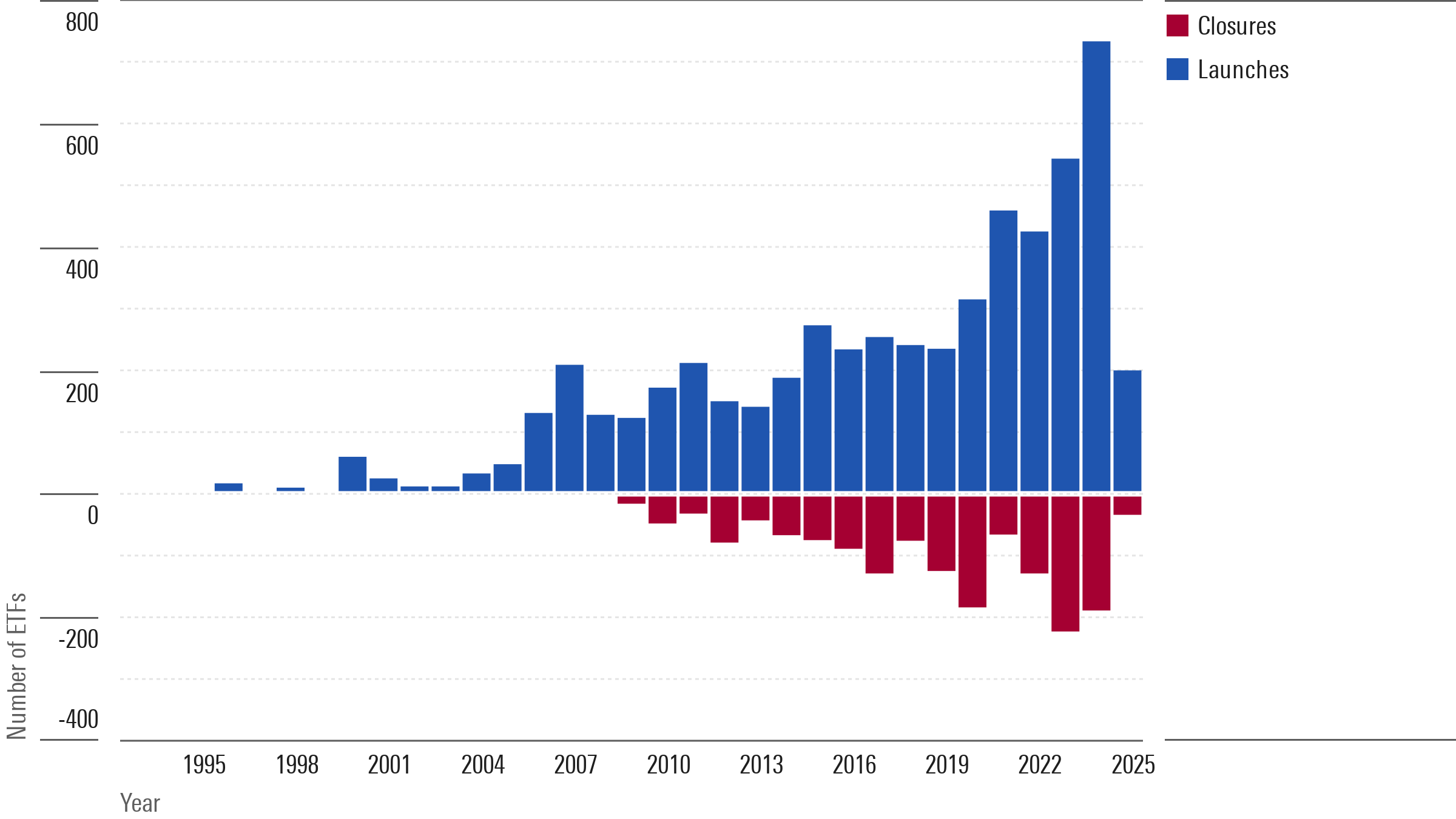

It wasn’t just Vanguard pushing into broad-market index-tracking ETFs. Competitors followed with their own. State Street, Charles Schwab, iShares, and others eventually created similar ETFs tracking broad stock and bond indexes that essentially provided similar, if not identical, risk/reward trade-offs. ETFs were off to the races. The chart below shows that more and more have entered the world year over year.

The ETF Business Cycle

Eventually, broad-market ETFs became common. Investors could (and still can) go to many of the large providers and build a globally diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds for a fraction of what many mutual funds charged. They largely competed on costs. The ETFs with the lowest expense ratios were the most attractive. That fostered intense competition and naturally drove expense ratios lower and lower over time.

Investors got a great deal, but many smaller ETF providers started to find it difficult to compete against the biggest firms offering the cheapest ETFs. Lowering expense ratios also meant that even the big firms faced problems growing profits from the meager fees they charged.

From an ETF provider’s perspective, creating new ETFs with different risk/reward profiles solves two problems. It’s a new story to sell, and they can charge higher fees for an investment that strives to outperform the market rather than mimic it.

Strategic-beta ETFs fit that mold in the mid-2000s. These index-tracking ETFs went a step beyond simple broad-market indexes. They attempted to copy the investment styles of active managers (value, growth, dividends, low volatility, and so on) and repackage them into neat rules-based portfolios. That gave ETF providers plenty of room to develop new investment strategies, for better or worse.

The years following the 2008 global financial crisis were fertile ground for strategic-beta ETFs. They surged in popularity throughout the 2010s. But the novelty started to wear off as the decade ended. The best of breed had emerged by that point—those that gave investors what they wanted and charged a reasonable fee. The money flowing into others stagnated, and many more shut down after they failed to perform well and grow larger.

That cycle is emblematic of the ETF business. Novelty grips investors, and ETF providers meet the demand with new ETFs. Over time, investors sort the best from the worst. The best stick around, the others slowly die off. Then a new trend comes along, and the cycle repeats. Similar circumstances fell upon thematic ETFs and sustainability ETFs over the past few years and the cycle will likely repeat with other trends as they come along.

Today, several fads are starting to work their way through the ETF business cycle. The most promising has been active managers migrating to ETFs from mutual funds. A lot of good investment strategies currently tied up in mutual funds could benefit from the tax efficiency and lower fees enabled by the ETF vehicle.

Solutions Looking for Problems

Other ETFs, such as those focused on cryptocurrencies, niche themes, and single stocks, raise big red flags. Many exploit investors’ worst emotional tendencies to gamble on a potentially big payoff. The providers creating these ETFs are playing the same game. They’re blasting a swath of speculative ETFs onto exchanges and betting that one or two perform well and become wildly popular. One or two big hits would be more than enough to justify the costs and effort of launching a bunch of duds.

More and more of those ETFs are coming out every day, so navigating today’s swampy ETF ecosystem can be a challenge. Asset managers have a lot of compelling stories to encourage you to buy their latest and greatest ETF. In practice, it isn’t that difficult to narrow the field down to better long-term options.

About 4,000 ETFs traded on US exchanges at the end of March 2025. Simply focusing on those that are sufficiently large or those with at least $1 billion eliminates many of them. Only 738 ETFs (19%) meet that standard.

The $1 billion threshold is a bit arbitrary, but it goes a long way to avoid the most speculative and questionable ETFs available. Size also confers some advantages. Large ETFs are more likely to be profitable for the provider, so they’re far less likely to shut down. And most gained their prominence over time. They tend to have longer track records, which can provide some valuable insight about how they perform in different environments.

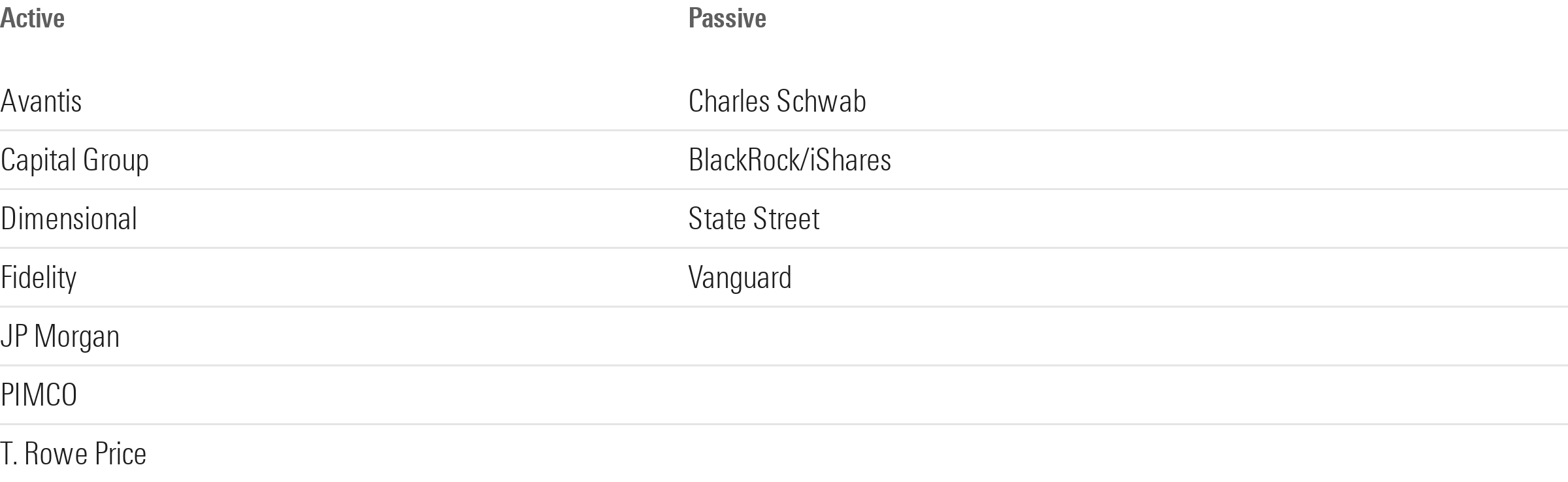

This universe of large ETFs can be fine-tuned a little more. Focusing on Morningstar’s top asset managers, or those with Above Average and High Parent ratings, culls that list down to just 461. Those asset managers are listed in Exhibit 2. They have ample resources, established management teams, and usually provide ETFs that rate well within Morningstar’s framework.

This wasn’t a perfect exercise, and exceptions were plentiful. It’s simply meant to demonstrate that very few ETFs have the chops to survive and outperform over the long haul.

ETFs have slogged through multiple cycles over the past three decades, but the north star for success hasn’t changed. Low-fee ETFs following sensible and repeatable investment processes have proved themselves to be the most robust and best-performing over long stretches.

Most of the big investment problems, such as increasing access to markets and cutting fees, have been solved, and ETFs enabled a lot of that. New ETFs with good long-term merit are increasingly rare. Exercise caution when looking at the latest choices.