Facing cash crunch amid slowing economic growth and falling land sales, China has turned to a crackdown on investors’ offshore gains to generate a new stream of revenue. Investors are likely to turn to US markets to escape the crackdown.

Facing cash crunch amid slowing economic growth and falling land sales, China has started a crackdown on investors’ offshore gains to generate a new stream of revenue. But it may prove to be counterproductive in multiple ways.

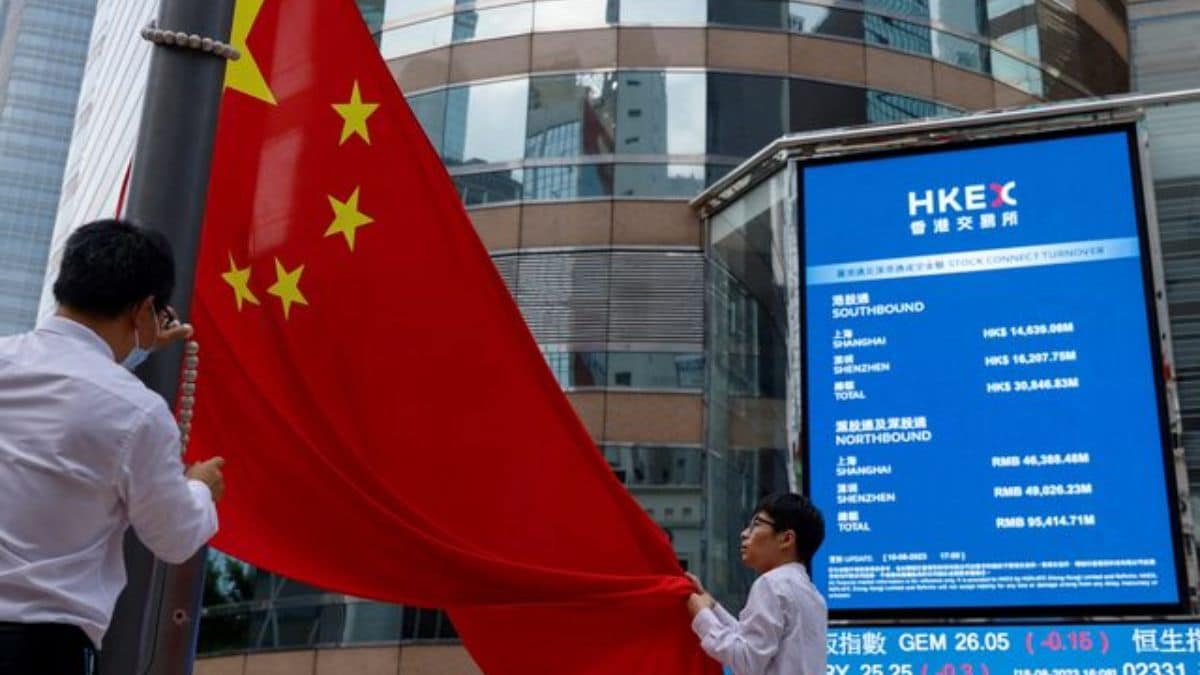

Chinese authorities are making public and direct calls to investors to declare and pay their taxes on their overseas investments, and they are using the Common Reporting Standard, an OECD-backed framework to tackle global tax evasion, to hound investors, according to Financial Times.

The crackdown is severe major economic hubs like Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Shandong, the newspaper reported.

China is in the grips of an economic slowdown, with the economy growing at 5.3 per cent in the first half of 2025. It is projected to grow this year at 4.6 per cent and miss the target of 5 per cent. Last month, the industrial output growth fell to 5.7 per cent from 6.8 per cent the previous month and factory fell to 6.2 per cent, the lowest since November 2024. The producer price index (PPI) fell 3.6 per cent year-on-year in July to a two-year low, suggesting factory-gate deflation.

Amid such a slowdown, China has turned to a crackdown on investors, but observers say that it could backfire.

How could China’s tax crackdown backfire?

Investors who spend 183 days a year in mainland China are required to pay 20 per cent tax on their global income.

However, China lacked the system and staff to charge that tax, but now it is increasingly enforcing it as it is under pressure to find new revenue streams to make up for falling revenue from traditional sources like land sales and factory production.

In 2018, China adopted the Common Reporting Standard, an OECD-backed framework to deal with global tax evasion, which allowed it to tap into financial account information, including balances and contact details, from banks, brokerages, and asset managers in 120 jurisdictions.

This can, however, backfire in two ways.

One, many investors are considering closing their accounts with Chinese brokerages and shifting to American platforms, according to FT.

“I’m sure that in my lifetime the US and China will not work together, they will not share information. I’m betting on that,” an investor told the newspaper.

Two, such a crackdown to tank investors’ confidence in China.

“Ultimately, this is a confidence issue. When a jurisdiction enforces taxes, it can signal that the state is lacking stable and rich tax sources. This perception, in turn, can undermine investor confidence,” Eugene Weng, a lawyer at Shanghai-based Wintell & Co, told the newspaper.