School districts, state leaders, and education experts continue to sound the alarm that the Trump administration’s hold on $6.8 billion in federal funds Congress already allocated for education will disproportionately harm students from low-income families, students with disabilities, and English learners.

The Trump administration notified states last week that seven federal education programs are currently under “ongoing programmatic review” despite a July 1 disbursement date enshrined in federal law.

The federal government distributes money for those programs using formulas that prioritize school districts with high concentrations of poverty.

So if the administration doesn’t eventually release the $6.8 billion it withheld last week, school districts with high concentrations of students of color and students from low-income families stand to lose several times more dollars per pupil than districts with low concentrations of those student populations, according to an analysis of federal spending data for more than 9,000 districts across 46 states by the left-leaning think tank New America.

The sudden absence of expected federal funds has already cost some educators their jobs. In Missouri, the Laclede Literacy Council laid off 16 of 17 staffers after the Trump administration didn’t give out $715 million nationwide for adult education. A summer camp serving 150 children in Thomasville, Ga., will run out of federal funding for academic enrichment programs July 11—cutting off services for students and pay for staff two weeks before the current session is set to end.

“It’s pretty disheartening to think about states helping districts plan strategically against academic outcomes based on what seems to be certain funding, and then have that funding just suddenly whipped away,” said Kevin Huffman, who served as commissioner of education in Tennessee from 2011 to 2015 under then-Gov. Bill Haslam, a Republican, and now owns a high-impact tutoring company that partners with school districts nationwide. “It feels very pointless.”

Congress stays largely quiet as states and districts struggle

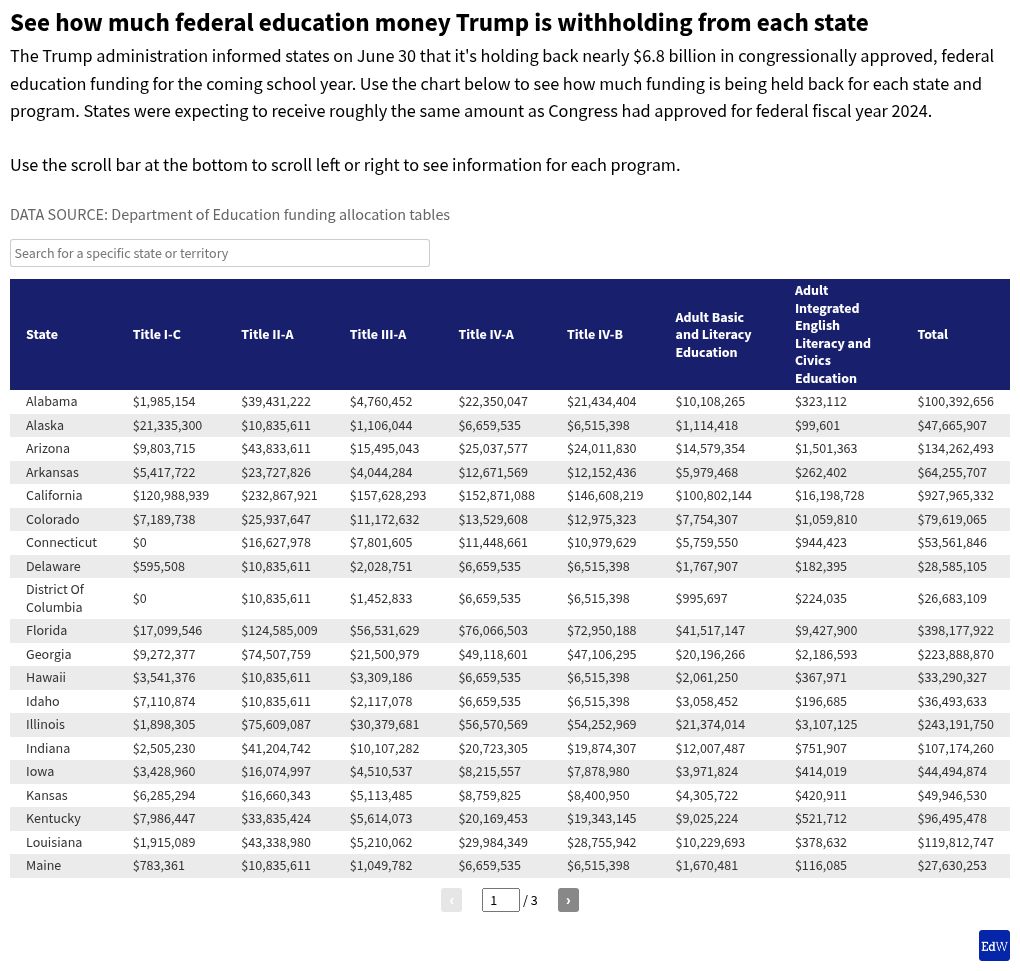

State education agencies found out June 30 through an unsigned three-sentence email from the U.S. Department of Education that they wouldn’t be receiving expected funds the next day for five programs for K-12 students and two programs for adult learners:

- Title I-C for migrant education ($375 million)

- Title II-A for professional development ($2.2 billion)

- Title III-A for English-learner services ($890 million)

- Title IV-A for academic enrichment ($1.3 billion)

- Title IV-B for before- and after-school programs ($1.4 billion)

- Adult Education basic grants ($629.6 million)

- Adult Integrated English Literacy and Civics Education grants ($85.9 million)

The announcement, foreshadowed for weeks but delivered with minimal explanation, has drawn stern rebukes from the governors of Arizona, Massachusetts, and Oregon; state education chiefs in Alabama, California, and Michigan; and a broad coalition of education organizations that represent teachers, district leaders, principals, and other school employees and advocates.

“There is no good-faith legal basis for withholding these funds,” wrote the Committee for Education Funding, a coalition of advocacy groups, in a July 2 letter to Congress.

At least 600 districts will lose more than $1 million each from the loss of four of the seven halted programs, New America researchers Zahava Stadler and Jordan Abbott report in the analysis published July 7.

Those cuts affect districts in every state. The Los Angeles Unified School District—the nation’s second largest—will lose $82 million from those four programs. Schools in Florida’s Miami-Dade and Broward counties will collectively lose more than $57 million for their combined 585,000 K-12 students. And in West Virginia, the 25,000-student Kanawha district will lose $19 million.

Democratic lawmakers on House and Senate appropriations and education committees have called on Trump to immediately release the funds and accused the administration of flagrantly violating the law.

Republicans who chair those committees have also called on the administration to release the funds.

“I strongly oppose the administration’s decision to pause the delivery of education formula grant funding to states and local school districts across the country,” Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, who chairs her chamber’s appropriations committee, wrote in a statement shared with Education Week. “… The administration should release these funds without any further delay.”

Rep. Tim Walberg, R-Mich., who chairs the House education committee, said he’s followed up with the federal Office of Management and Budget, or OMB, to ask for more information.

“It is my understanding that the administration is working to ensure these funds are being used to support students and make sure the civil rights of students and educators are not being violated within these programs,” Walberg said in a statement on July 7. “However, these funds were appropriated by Congress, and it is important that all funds Congress appropriated be promptly distributed.”

Spokespeople for Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., who chairs the Senate education committee, and Rep. Tom Cole, who chairs the House appropriations committee, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Federal agency says it’s reviewing spending for compliance with the president’s agenda

Many district leaders across the country have begun cobbling together contingency plans, or consulting with state education agencies on next steps. The Little Rock school district in Arkansas, for example, immediately froze all federally funded training programs and staff travel plans.

School districts may need to consider layoffs and other cuts if the situation doesn’t change, Eric Mackey, Alabama’s state superintendent of education, said during a July 3 panel discussion. Rethinking the federal role of education is a laudable goal, Mackey said, but “we can’t have that discussion about the 25-26 school year in July of 2025.”

OMB said the hold is part of “an ongoing programmatic review of education funding.

“Initial findings have shown that many of these grant programs have been grossly misused to subsidize a radical left-wing agenda.”

OMB and the Education Department haven’t said when the review will be complete, and they haven’t guaranteed the funds will flow once it is.

Even if they do, though, many districts will likely have already used local funds to keep priorities on track, if they haven’t already canceled some programs. If districts revert back to funding them with federal dollars, they could risk violating federal restrictions on “supplanting” state and local dollars with federal funds, said Brooke Olsen-Farrell, superintendent of the Slate Valley district in Vermont.

Districts also risk missing their windows of opportunity to hire staff they typically pay using the affected federal funds.

“There’s not going to be people to hire in November or December of a school year, and introduce them to systems that you’ve built around not having those people,” Olsen-Farrell said.

Here’s a look at groups of children and adults alike who stand be most affected if the funding Congress allocated for education doesn’t make it to districts.

Low-income students—and their families

Among the 9,000 districts New America researchers examined, those with more than 25% of students in poverty on average are losing 5.1 times more dollars per pupil from Titles II-A, III-A, IV-A, and IV-B—the largest K-12 funding sources the administration is holding back—than districts with fewer than 10% of students in poverty.

That gap is in part a product of the laws that govern these programs. Most federal funding programs for K-12 education aim to supplement budgets for districts likely to incur higher costs, including for serving high-need populations of students.

The loss of federal funding affects opportunities not just for low-income students, but for their families as well.

After-school programs funded with Title IV-B dollars provide students with enrichment programming—but parents also benefit from free child care.

Last summer, the Chicago school district partnered with a community nonprofit to offer an after-school program staffed by teachers in several neighborhoods. Denali Dasgupta, an early childhood education researcher who runs a data consultancy, sent her daughter there, giving her an extra hour to work from home four afternoons a week.

Her husband works overnight, which means she has to pay for child care whenever she’s not free to watch her kids during the day.

That summer program, she said, “was the difference between me being in the workforce full-time versus part-time.”

Many after-school programs could shut down beginning next month without Title IV-B funding, said Jodi Grant, executive director of the Afterschool Alliance, a nationwide nonprofit advocacy group.

“We expect this to hit when schools go back in session,” she said.

English learners

Federal law requires schools to provide equal educational opportunities to all students, regardless of their native language. More than 5 million K-12 students nationwide qualify for English-learner services.

Congress allocated $890 million for Title III-A in the fiscal 2025 “continuing resolution” approved in March. If that money goes away, school districts that serve English learners will have to find other sources of funding to continue offering services—or risk violating the law.

In dozens of districts losing more than $800 per pupil from the four programs New America analyzed, English learners make up more than 20% of the student population.

The program helps pay for a wide range of services, including salaries for teachers and instructional support staff. The Harrison school district in Colorado Springs, Colo., uses Title III funds to pay for a translation service that helps staff communicate more effectively with families. The district’s students speak 51 languages.

Superintendent Wendy Birhanzel told the Colorado Sun that the administration’s hold on Title III and other programs that serve immigrant students sends a concerning message that “these funds and these programs or the people in these programs aren’t important.”

Students with disabilities

The Trump administration sent the first of two scheduled installments of Individuals with Disabilities Education Act funds ($15.8 billion in total) to every state as scheduled on July 1. But that doesn’t mean students with disabilities will be unaffected by federal funding changes.

Out of 5.3 million English learners nationwide, roughly 16%, or 837,000, also qualify for special education services. Some students who qualify for migrant education services or attend federally funded before- and after-school programs also have disabilities. Both could experience disrupted services as federal funding streams dry up more quickly than districts expected.

Many special education directors rely on Title IV-A funds in tandem with IDEA funds to provide mental health support and other health services for students with disabilities, said Myrna Mandlawitz, policy and legislative consultant for the Council of Administrators of Special Education.

The cancellation of that program has been particularly confounding, Mandlawitz said, because it’s a block-grant program just like the one the Trump administration has proposed in an effort to consolidate 18 separate federal funding streams.

“That is a flexible pot of $1.3 billion already allocated for school districts that they can use in a variety of ways,” Mandlawitz said. “To say you’re not going to give that money out makes absolutely no sense given their philosophy” on flexibility for states to spend education funds as they see fit.

Private school students

Federal funds don’t just go to public schools. Because of federal requirements that public school districts ensure non-public school students within their boundaries receive “equitable services,” private schools also benefit from a portion of the allocations for each of the Title programs the Trump administration has withheld.

States sometimes allocate as much as one-fifth of their Title II-A and IV-A allocations for private schools, said Catherine Pozniak, a school finance consultant who works with school districts nationwide on federal grants.

Private schools, particularly those with small numbers of students, will likely have to cancel planned professional development and pare back programming for English learners if the Trump administration doesn’t release the Title funds it’s currently withholding, said Michelle Walthers, director of federal funds for the Archdiocese of Chicago. Walthers oversees the transfer of federal funds from Chicago schools to roughly 150 local Catholic schools.

“There’s a lot of schools that have smaller enrollments, they’re just making it,” Walthers said. “For them to be able to add on professional development [without federal funding], that would be a little difficult.”

Schools in Walthers’ purview particularly rely on Title IV-A funds for technology tools or to expand their academic offerings, she said.

The Title IV-A Coalition, an alliance of 40 organizations that support the program and its beneficiaries, says “its strength lies in how seamlessly it integrates with other federal programs to support planning, implementation, and student success.

“This disruption not only threatens the delivery of critical services but also erodes the trust districts place in a stable federal partnership,” the coalition wrote in a statement.

State education department staff

Many state education agencies receive large chunks of their annual funding from the federal government.

Most federal funding streams for education include “administrative set-asides”—small pots of money for states to employ staff that oversee grant allocations, communicate with districts when problems arise, and offer guidance on maximizing funds in legal ways.

The New Mexico education department, for instance, uses federal funds from the programs Trump has halted to pay salaries for roughly 10 state employees, according to an analysis by John Sena from New Mexico’s nonpartisan Legislative Education Study Committee. Districts use those funds to pay employ close to 180 people statewide, Sena’s analysis shows.

Huffman, the former Tennessee education commissioner, believes state education agency capacity will suffer without the halted funds—even as the Trump administration emphasizes shifting federal education responsibilities to states.

“It’d be one thing if this was planned for and there was discussion and the opportunity for people to think about, how do you go and appropriate additional money?” Huffman said.

But all but a handful of states have already approved their budgets for the upcoming fiscal year.

“The states have not allocated sufficient resources to run high-functioning” state education agencies without federal support, Huffman said.