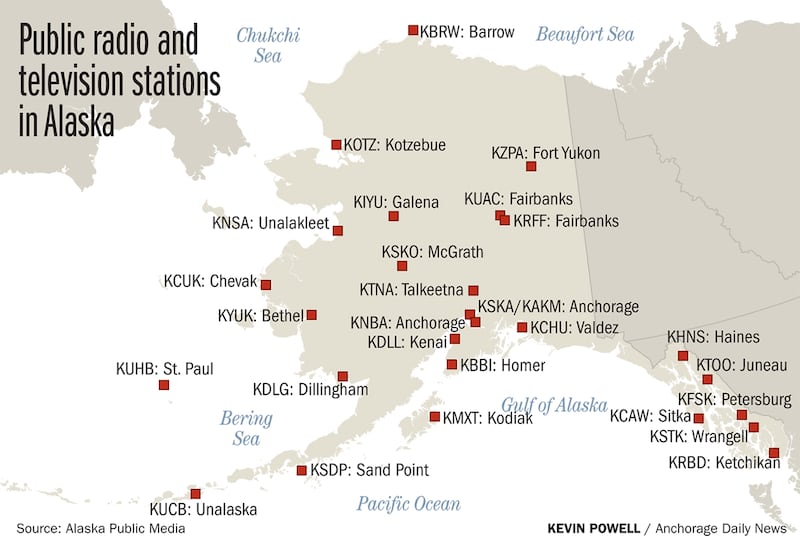

As the Trump administration works to end nearly all federal support for public broadcasting in the United States, the loss of that money for the state’s 27 public radio stations and four public TV stations could jeopardize remote Alaskans’ access to community connections and local and national news, and public safety, station managers across the state said this week.

Earlier this month, national news outlets reported that the White House drafted a memo asking Congress to rescind $1.1 billion in funds to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting — a nonprofit that Congress appropriates taxpayer dollars to for public media nationwide — for about the next two years. The memo leaves intact $100 million allocated for emergency communications, The New York Times reported. The unpublished memo — expected to be presented once Congress reconvenes Monday — gives Congress 45 days to approve the cuts or restore the spending, NPR reported.

President Donald Trump’s administration has called public media — particularly NPR and PBS — “a waste” of taxpayer dollars, saying it produces “radical, woke propaganda” with “zero tolerance for non-leftist viewpoints,” according to a White House statement Monday. Americans spend an average of $1.60 per year on public broadcasting through taxes, according to CPB.

While NPR receives 1% of its funding directly from the federal government, its close to 300 member stations rely on a much greater percentage, according to NPR. That includes stations across Alaska, which report they’re already strained without state funding. Gov. Mike Dunleavy has vetoed state funding toward public broadcasting each fiscal year since 2019.

“In many parts of Alaska — and communities throughout the country — public media is often the only locally operated, locally controlled broadcasting service,” said Ed Ulman, president and CEO of Alaska Public Media, in testimony before the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability in Washington, D.C., in March. “We are more than nice to have. We are essential, especially in remote and rural places where commercial broadcasting cannot succeed.”

Although Alaska has fewer public television stations — KAKM in Anchorage, KTOO in Juneau, KYUK in Bethel and KUAC in Fairbanks — they receive higher levels of federal funding compared to radio, Ulman said. That’s because television costs more to produce, and has a wider reach.

In Bethel, KYUK’s main radio broadcast reaches about 13,500 predominantly Yup’ik residents throughout the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in Southwest Alaska. Between their television and radio station, federal funding makes up about 70% of KYUK’s operating budget each year, said Kristin Hall, interim general manager.

“I would avoid closing at all costs, but that would mean a drastic change in our operations,” Hall said of a potential stop in federal allocations. KYUK currently broadcasts local news in English and Yup’ik three times a day with a news team of three full-time reporters, and a few part-time editors, translators and multimedia team members. Hall said the station’s robust coverage of a region roughly the size of South Dakota “wouldn’t be as realistic” without the funding to support it.

KCAW in Sitka depends on federal funding to power about 30% of its annual budget, said manager Mariana Robertson.

Most of it helps pay to maintain specialized radio equipment that allows the station to stay on air and transmit information to eight communities throughout Southeast Alaska in the event of power loss.

“We’ve had a fatal landslide here in Sitka, we’ve had so many warnings, and so those are the kind of instances in which we really want to be on the air, sharing information with our community,” Robertson said. “That’s the investment in public safety (and) in our communities that the government is making when it funds through CPB funds.”

In the absence of federal funds, Robertson said the station will seek philanthropic support to try to make up the difference. Already, donor contributions make up 40% of their budget.

“We’re really asking our community for so much already, so we’re going to look to other sources of philanthropy,” Robertson said. “But really, we need this money.”

Juneau’s public radio and television station, KTOO, will be losing about a third of its budget, said General Manager Justin Shoman. Some employees traveled to Washington, D.C., in February to talk with lawmakers, and KTOO has posted a “Federal Funding” page on its website to communicate to listeners and members about the impact of a loss of funding, he said.

“We are trying to be very proactive in our approach to influencing this decision from an organizational perspective,” Shoman said.

In Utqiagvik, KBRW General Manager Jeff Seifert said that the loss of 40% of the station’s budget — the amount filled by CPB funding — could eventually mean lights out for their already bare-bones, roughly five-person operation.

“I’m thinking we could survive maybe two years,” Seifert said, referring to the station’s “nest egg” savings. “But everything is so expensive up here, there’s just no way to make up for that kind of a loss. Just keeping the lights on is hugely expensive. Probably we’d reduce our services to almost nothing.”

For a station like KBRW, which serves seven additional villages and Prudhoe Bay in an area that spans 95,000 square miles, people rely on the radio for everything from birthday wishes called in by a loved one, to local government meetings, to weather reports that could save lives, Seifert said.

“Right now is our spring whaling,” Seifert said. “Our whalers are out on the edge of the ice. They keep KBRW on 24 hours a day.” For company and entertainment, sure, but also for wind condition reports that inform how the sea ice might move and crack, he said.

Many of Alaska’s rural radio stations are the main source of local news in their area.

KUCB in Unalaska, a station that would lose about 40% of its budget if Congress moves forward with the Trump administration’s proposal, is one of them, said General Manager Lauren Adams.

“We’re the only ones providing news here in Unalaska, with reporters who live here year-round,” she said. Federal cuts would inevitably force staff reductions, which would decrease local reporting and change how KUCB sounds, she said.

“We would probably be more of a repeater station than a local station,” Adams said. “We would basically run local as often as possible, but a lot of our content would not come from Alaska.”

Most radio stations in Alaska have already received the federal funding that will carry them through the end of the federal fiscal year, which runs through September, Seifert said.

But a challenge is drafting a budget now that will take effect July 1, with unreliable funding sources, Seifert said:

“We’re kind of lost as to, how do you do a budget when you don’t know where 40% of the money is going to come from?”