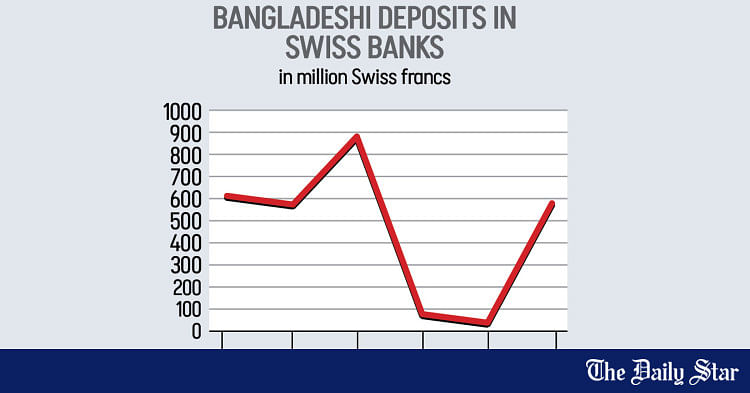

Bangladeshi-linked funds parked in Swiss banks surged to 589.5 million Swiss francs, or about Tk 8,800 crore, in 2024, their highest level in three years, according to data released by the Swiss National Bank (SNB) yesterday.

The sharp rise, which marked a stark reversal after two years of steep decline, coincided with a tumultuous political transition in Bangladesh last year. Analysts said the upheaval may have triggered a wave of capital outflows as politically connected individuals sought to stash their assets abroad.

This increase in offshore funds during a year of uprising raises questions about Bangladesh’s ability to stem suspicious outflows.

“It’s not just about Swiss banks any more. From Dubai to Ireland, new safe havens are emerging where you can buy properties, open accounts, and move money more discreetly,” said Zahid Hussain, former lead economist at the World Bank’s Dhaka office.

“The secrecy that once defined Swiss banking is no longer what it used to be,” he told The Daily Star.

“A deposit in a Swiss bank coming from the UK may be legal, but that doesn’t mean the money wasn’t laundered earlier through under-invoicing in trade. And we can’t rule out that these funds passed through legal channels before landing in Swiss banks, especially given how sophisticated illicit flows have become,” said Hussain, who was part of a government-formed panel that authored a white paper on the state of Bangladesh’s economy.

A total of $234 billion was siphoned off from Bangladesh between 2009 and 2023, according to the white paper published in December last year. As per the report, the laundered money was sent to or routed primarily through the UAE, the UK, Canada, the US, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore and India, as well as a number of tax havens.

Deposits linked to Bangladeshi nationals and entities in Swiss banks jumped 33-fold in 2024 from the previous year, when holdings had dropped to a record low of just 17.7 million francs. The deposits declined sharply also in 2022, following a post-pandemic peak of 871 million francs in 2021 amid growing global scrutiny of illicit financial flows.

The SNB data, released annually, tracks funds held in all currencies by Bangladeshi nationals, residents, or corporate entities in Swiss banks under the category “Banks in Switzerland”. It does not disaggregate by type of depositor or specific purpose of the funds.

Swiss banks have historically been associated with financial secrecy, leading to concerns about their role in facilitating illicit money flows. While recent reforms have increased transparency and cooperation with international authorities, Swiss banks continue to be scrutinised for their handling of funds potentially linked to money laundering.

From 2015 to 2020, Bangladeshi deposits in Swiss banks typically ranged between 480 million and 660 million francs. The latest spike is expected to draw renewed scrutiny, particularly as Bangladesh’s interim government has made financial transparency and asset recovery a core part of its reform agenda.

“Based on global experience, the recovery rate for illicit outflows is just around 1 percent,” Hussain said. “To get the money back, you have to win legal cases in both countries — where it originated and where it ended up. It’s not just about knowing the money left illegally — you have to prove it in court, twice.”