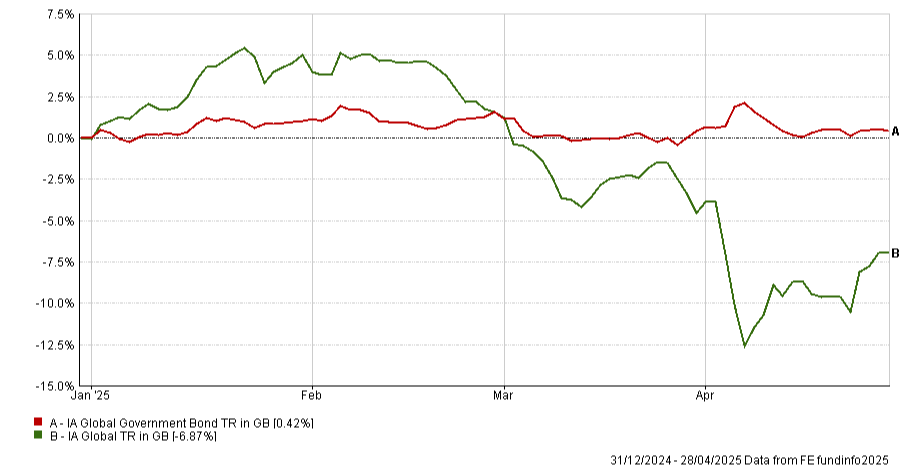

Many investors take the view that bonds exist in a portfolio to dampen volatility and to perform well when equity markets are roiled.

Such an outlook faced an existential threat in 2022, as rapidly rising interest rates led to drops in both equity and bond markets.

The chart below shows the story of 2025 to date has been one of the old order restored, with government bonds and equities moving inversely.

Over the longer-term, bonds have been a curiosity in portfolios, with the years immediately after the global financial crisis characterised by record low, and sometimes negative, yields, correlations with equities, and investors owning bonds for the potential capital gains, rather than the income.

From all of this uncertainty the private loans market emerged and grew.

Initially such funds were the preserve of the institutional investor, but, more recently, firms such as Pimco, Aviva and Pictet have begun to explore the asset class for advised clients.

Andreas Klein is head of the private credit business at Pictet. He says the concept of such funds first emerged in the years immediately after the global financial crisis, as banks, racked with liquidity problems, pulled back from corporate lending.

Subsequently, regulators created a new framework which meant banks wishing to own riskier assets, such as bonds with a credit rating below investment grade, needed to retain more capital.

Exodus

According to Klein that prompted an exodus by banks from certain parts of the lending market and the entry into those markets by asset management firms eager to deploy client capital.

He says when such funds first came on to the market, the typical client was a pension fund, insurance company or endowment, as those investors do not need daily liquidity from their investment portfolios.

Private credit should not be described as a liquid asset class.

He put the total size of the global private credit market at between $2-3tn, of which around 40 per cent is in European assets.

But he says because the market has matured in recent years, “there has been an impetus towards the mass affluent and high-net-worth client.

“That does bring certain nuances which have to be considered. There are liquidity concerns for many of those investors and private credit should not be described as a liquid asset class.”

Aaron Hussein, global market strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, says: “The rise of evergreen and semi-liquid private debt vehicles is transforming how the asset class is accessed and implemented.

“These newer structures offer regular subscriptions and redemptions, reduced capital call complexity and more stable return profiles — making them far more compatible with private wealth platforms, family offices and smaller institutions.

Significant shift

“At the same time, regulatory developments such as the UK’s LTAF [long-term asset funds] regime and ELTIF 2.0 [European long-term investment funds] in the EU are opening the door for broader retail and high-net-worth participation, marking a significant shift in how private markets are delivered to end investors.”

Mark Versey, chief executive of Aviva Investors, says his firm is keen to grow its presence in the private assets space, including through work it is doing with the FCA to explore how LTAFs can be included in advised portfolios.

He believes the returns achievable from private debt and equity are superior to those achievable from public assets without extra risk being taken.

Versey says: “The cost is reduced liquidity, and that needs to be advised, so I don’t think its something non-advised clients should be accessing.”

It perhaps begs the question, what sort of assets do these funds own?

Pimco recently brought to market a private credit fund aimed at UK advised clients among others.

That strategy will be run by Kristofer Kraus, who says private credit portfolios can generally be divided into two buckets — one is the traditional lending to corporate entities, and the other is asset-backed lending.

The latter is an area where he has seen growth. This type of investing covers lending against mortgages, also known as mortgage-backed securities, and against assets such as aircraft.

He acknowledges clients can access those strategies now, typically via investment trusts that are quoted on the stock exchange, and so don’t have the same liquidity issues.

Kraus says the capital provided by such funds is a very small part of the overall capital required in those markets, but also that the relatively less liquid way to access those investments generates higher returns.

Portfolio construction

The notion of receiving an extra slice of return in exchange for owning an asset that is less liquid is known as an illiquidity premium, and both Kraus and Klein feel it is central to the investment case for private credit.

Klein says the premium one currently receives for owning a less liquid bond is about 2 per cent in terms of yield above the rate on a similar bond that is listed.

More traditional bond funds focus on achieving returns through the management of duration, the measurement of the sensitivity of a bond price to interest rates, and credit risk, the potential for the issuer of the bond to default on the payments.

Do strategic bond funds still have a role to play in portfolios?

Some fund managers pay more attention to one or other of those factors depending on the prevailing economic climate or the expertise of the fund manager.

Private debt almost always has a credit rating below investment grade, meaning a credit rating of below BBB, says Klein.

But his view is the bonds may not in themselves have a higher risk of default, as “each deal to lend money in private markets is bespoke”.

Because private credit is not daily priced, the sensitivity at the portfolio level to movements in interest rate expectations should be minimal, says Klein.

However, Kraus says because many of the bonds on the private credit market are issued with a floating interest rate — a rate that tracks the base rate — the price of such instruments is likely to be sensitive to interest rate expectations, as people are more likely to want to own a bond with a rising interest rate if the base rate is rising.

Kraus says he has been a big buyer of UK mortgage bonds, but that even within the asset class, the risk level of which varies by type of lender, it creates a credit risk curve similar to that which exists in publicly listed bond markets.

He feels the one area of private credit markets that may be overpriced is banks selling on parcels of debt.

Funds taking secondary lines of private debt are more interesting, in our view

The availability of suitable product rather than qualms about the asset class, has so far restricted Simon King, chief investment officer at Vermeer Partners.

He says: “This is an area that interests us but as usual it remains difficult to get exposure to high quality assets at a reasonable cost. We are always wary that we are being offered the stub end of the sponsors book given their in-house clients will be paying higher fees.

“If we take product from a consolidator who is buying other funds, then the cost becomes prohibitive. Funds taking secondary lines of private debt are more interesting, in our view.”

David Thorpe is senior investment editor at FT Adviser