OXFORD, Miss. – Two University of Mississippi graduate students got to pursue their research goals this summer thanks to a gift from alumna Frances Permenter Smith, a longtime friend of the university.

Gianna Mitchell and Nicholas Nighswander, both first-year doctoral students in biology, are completing their summer research with funding from Smith’s $6,000 gift to the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Research.

“Conservation is very important to me,” Smith said. “The incredible work these kids are doing just struck me, and the thought that some of them may not be able to do their work because of limited funds led me to want to support them.

“It made me feel like I was doing something not only to help the students, but to make a difference in the world.”

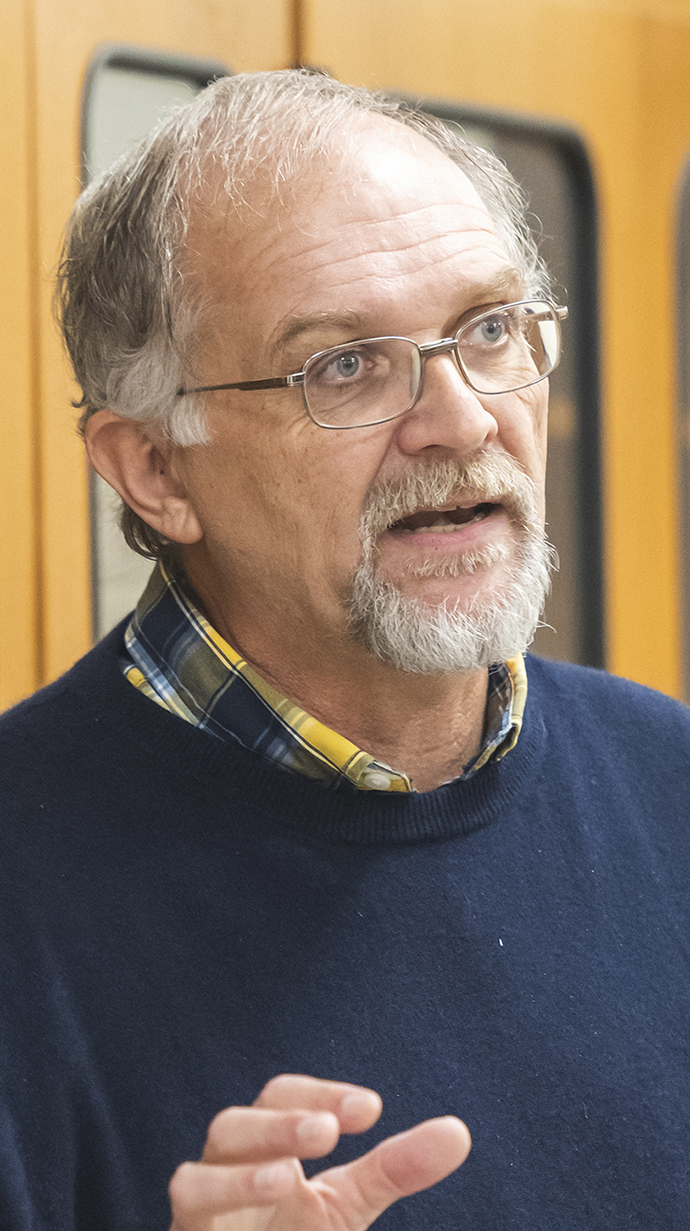

Nearly every graduate student must conduct research to complete their degree, but funding that research is often difficult, said Richard Buchholz, Ole Miss biology professor and the center’s director. The center’s annual summer research grants help fill the gap.

“These students have to develop these projects for their degrees, and one of the biggest challenges is getting started,” he said. “In every graduate program, there are some things that might be funded directly by their advisers, but often there are bits and pieces that the students are carving out as their own, and there may not be funding for that.

“That’s what’s so critical about this funding: it allows the students to conduct their research and, ultimately, to get their degrees.”

Mitchell, from Naples, Florida, spent the first three weeks of summer studying coral reefs in Florida, where she hopes to better understand coral bleaching.

Bleaching occurs when corals become stressed – normally because of increased water temperatures – and expel the tiny algae that live within their tissues. These algae have symbiotic relationships with corals, providing energy to the coral through photosynthesis.

Coral reefs provide critical infrastructure to plant and sea life, while also providing natural flood defenses to coastal lands and islands.

Gianna Mitchell (left), a first-year doctoral student in biology, examines octocoral samples during her summer research at the MarineLab in Key Largo, Florida. Submitted photo

“This was my first field season, and it was such a learning experience,” Mitchell said. “I really feel like it gave me the confidence to go back and do my next field study.”

“Without the CBCR, I literally could not have done that.”

Mitchell is studying how octocorals – a subclass of corals that are surviving the increased water temperatures better than hard corals – get their energy. Understanding how octocorals survive environmental stressors could inform conservation efforts, she said.

“For me, it’s a very personal thing,” said Mitchell, who grew up diving in Florida and has been a certified scuba diver for nearly a decade. “The ocean has always been a part of my life, and I always have that in the back of my head driving me to learn more.”

Research experiences like this one are crucial to the development of young scientists, said Tamar Goulet, professor of biology and Mitchell’s research adviser.

“She’s asking original research questions, then designing the study and figuring out how to address those questions, collecting and analyzing data and, ultimately, reaching conclusions and writing about it,” Goulet said. “What I mean by that is she is learning how to be successful in her career – how to think, how to see the big picture.

“That’s what this grant has enabled her to do: the work. So, it really made a difference for her.”

Future scientists must have field experience to be successful, but going out into the field can be costly, Goulet said.

“Those student grants are fundamental for student success,” she said. “You know, the saying ‘Success begets success’ really applies to funding. Gianna is now hitting the ground running in the fall semester with the data, and this early success is going to help her write grants for more funding.

“This grant made her summer, and it’s setting her up for success for the rest of her time here.”

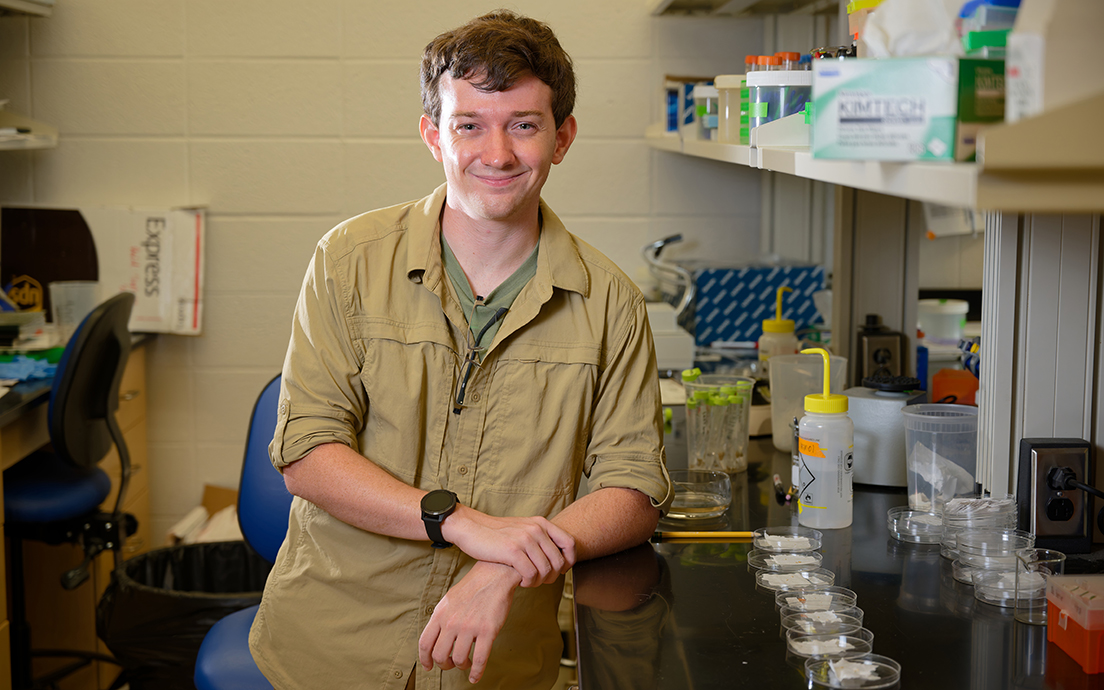

Nighswander, from Goreville, Illinois, is traveling between Oxford and northwestern Arkansas this summer to study genetic diversity in insect populations in the Ouachita and Ozark mountain ranges. As human development – buildings, roads and other infrastructure – encroach on these habitats, the insects often have trouble diversifying their gene pools, meaning they can become inbred.

Saproxylic insects – such as the termites and darkling beetles Nighswander collected on his last trip to Arkansas – perform crucial functions for forest health by recycling nutrients from dead trees back into the ecosystem. But inbred populations are more likely to be susceptible to disease and to have health problems, which means the forest loses its recyclers.

“But it’s not just insects; this applies to larger animals as well,” Nighswander said. “Insects are a good indicator for how gene flow works in other animals, because I can collect hundreds of them, whereas something larger would take a lot more money, a lot more time, a lot more everything.

Nicholas Nighswander, a first-year doctoral student in biology, is studying how elevation and human infrastructure can impact genetic diversity in saproxylic insects. Photo by Hunt Mercier/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

“If we can understand gene flow in the insect population, we can scale that up and really understand the forest health overall.”

Nighswander is studying the insects’ DNA to determine how genetically diverse they are and, hopefully, inform future conservation efforts for endangered animals found in mountain environments.

“Even things like the elevation of the mountain can impact genetic diversity,” Nighswander said. “All these things are just compounding on top of each other and overall making it a lot more difficult for these insects to survive.

“Understanding the problem is going to be a long process and is going to take a lot of time. I’m just glad that there’s organizations like the CBCR that can help fund this kind of project.”

Both Mitchell and Nighswander’s work focuses on conservation, a prerequisite for any project the center funds. But that doesn’t mean the student must study biology.

“We’ve had students from geology, students from chemistry; they don’t necessarily have to be biologists,” Buchholz said. “There are all sorts of disciplines that study conserving nature and understanding the diversity of life. Any graduate student can apply.”

Nicholas Nighswander is studying darkling beetles, one of the many forms of saproxylic insects – insects that feed on dead wood – whose genetic gene pools can be affected by human activities. Photo by Hunt Mercier/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

But gifts like Smith’s are crucial to continuing the center’s work and the students it supports.

“With the state of research funding being what it is, we could not do this without donations like this one,” Buchholz said. “Her donation gave us the opportunity to keep it going for another year, and that was huge.”

For Smith, contributing to the student’s success was at the intersection of two passions.

“I encourage alums to talk with professors about what their students are working on, find a project close to their hearts and donate towards it,” she said. “For example, the scuba divers in my family have been concerned about the coral reefs for some time, so funding further study on this was personal for me. A true win-win.”

To support the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Research, click here or contact Richard Buchholz at byrb@olemiss.edu.

Top: Gianna Mitchell, a first-year doctoral student in biology, collects coral samples in the Florida Keys. Mitchell’s research, which looks at how octocorals get their food sources, is funded by a summer research grant from the university’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation Research. Submitted photo