Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

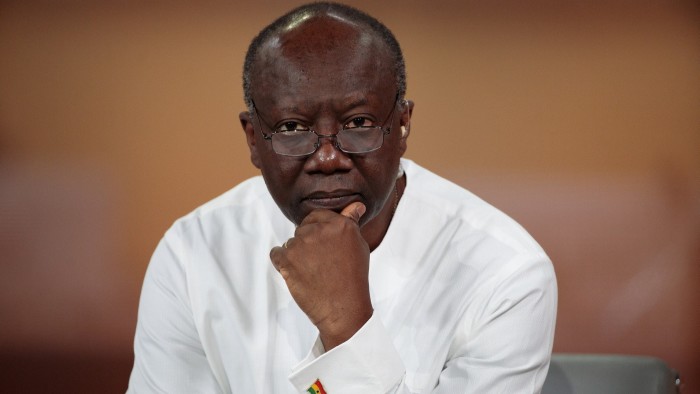

Ken Ofori-Atta has worn many hats in his long career as an investment banker, entrepreneur and until last year Ghana’s Davos-pleasing finance minister. Now he has a new one: a wanted man on Interpol’s red list.

Ofori-Atta, 65, who has been seeking medical treatment in the US, is wanted to answer charges of “using public office for profit” during his 2017-2024 tenure as finance minister, the longest in Ghana’s history. He denies all charges.

The Interpol red notice is the latest salvo in a legal drama between Ofori-Atta and the Office of Ghana’s Special Prosecutor (OSP), which declared him a “fugitive” in February as part of a sprawling anti-corruption drive launched by President John Mahama, who took office in January.

Ofori-Atta told the Financial Times before the Interpol red notice was issued that he was “puzzled and dismayed” by the turn of events. He had initially asked the prosecutor to speak to his lawyers given that he would “be out of the country for the next few months”.

Ofori-Atta said he was not the “originating nor implementing minister” in four of the five cases brought up by the prosecutor, relating to government contracts in power, petroleum and health.

The former finance minister is also wanted in relation to an estimated $58mn of public funds spent on Accra’s ill-fated National Cathedral project, which was abandoned two years ago. A devout Christian who once led a prayer session for the success of a eurobond offering, Ofori-Atta personally backed the project.

The National Democratic Congress won December’s presidential election promising to stamp out corruption that had allegedly taken hold during the previous administration of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), of which Ofori-Atta was a leading light.

The NPP government, headed by Nana Akufo-Addo, Ofori-Atta’s cousin, had come to power promising a squeaky-clean technocratic administration, but it was forced to default on the country’s debt in December 2022 and seek a $3bn IMF bailout.

As finance minister, Ofori-Atta blamed the Covid-19 pandemic and a sharp currency depreciation for the default, but critics say government profligacy was also a factor.

Operation Recover All Loot (Oral) was initiated by Mahama to document alleged cases of corruption. A report submitted in February claimed more than $20bn had been stolen.

Bright Simons, head of research at the Imani think-tank in Accra, said Mahama’s anti-corruption campaign was a response to public anger at a “deepening sense of impunity” among the political elite. “High-profile prosecutions are central to this strategy,” he said.

Ghana is considered one of Africa’s most successful democracies, with a reasonably buoyant economy despite the 2022 default.

But since the corruption probe was launched, the capital Accra has been gripped by fear. Officials who served in Akufo-Addo’s government have been privately wondering whether they would be next on the special prosecutor’s docket. Many describe the campaign as vindictive and attention-grabbing.

At least one former high-ranking Akufo-Addo adviser has taken to driving around Accra with private security to ward off police attention.

Ofori-Atta is the highest-profile, but not the only, former government official to be caught in the widening probe. In March, the private residence of Ernest Addison, former central bank chief, was raided at dawn by some 15 heavily armed soldiers searching for “vaults” he allegedly kept at home. No vaults were found, according to local media reports.

Imani’s Simons said Mahama, whose previous administration from 2012-17 was itself accused of corruption, had not made the “substantive changes” needed to root out the lingering perception of pervasive graft. The think-tank, and civil society as a whole, has called for greater transparency around government spending.

It is also pushing for merit-based appointments, “lifestyle audits” of those in government roles who live lavishly, and for unexplained wealth orders to be built into the civil service code.

“These are a few of many governance reforms demanded over the years by civil society organisations that have always been brushed aside [in favour of] cosmetic actions,” Simons said.

An initial thaw in relations between Ofori-Atta and the OSP, headed by Kissi Agyebeng, broke down when the former finance minister sued the OSP, citing unlawful treatment and demanding the removal of “damaging” content from the agency’s social media accounts.

At a recent press briefing, Agyebeng said he had rejected Ofori-Atta’s offer to appear at a virtual hearing.

“We want him here physically, and we insist on it,” Agyebeng said. “A suspect in a criminal investigation does not pick and choose how the investigative body conducts its investigations and the methods suitable to him and his convenience.”

Ofori-Atta did not immediately respond to a request for comment.