But if a lawmaker happens to lead a nonprofit — as is the case for a handful of lawmakers on Beacon Hill — lobbyists and business interests have a third, more secretive way. Donations to nonprofits don’t require disclosure and are, therefore, essentially impossible to track.

The revelation spotlights a loophole in the state’s 30-year-old campaign finance law that allows lobbyists, who otherwise face $200 campaign contribution limits, to give whatever they want to a lawmaker soliciting donations to their nonprofits — a practice that is prohibited at the federal level and raises questions by experts about what should be disclosed.

It’s a well-used path. As hard as such giving can be to pin down, a Boston Globe review found that some of the state’s most influential lobbying firms and businesses with interests before the Legislature, are contributing thousands to some of the state’s most powerful players on Beacon Hill.

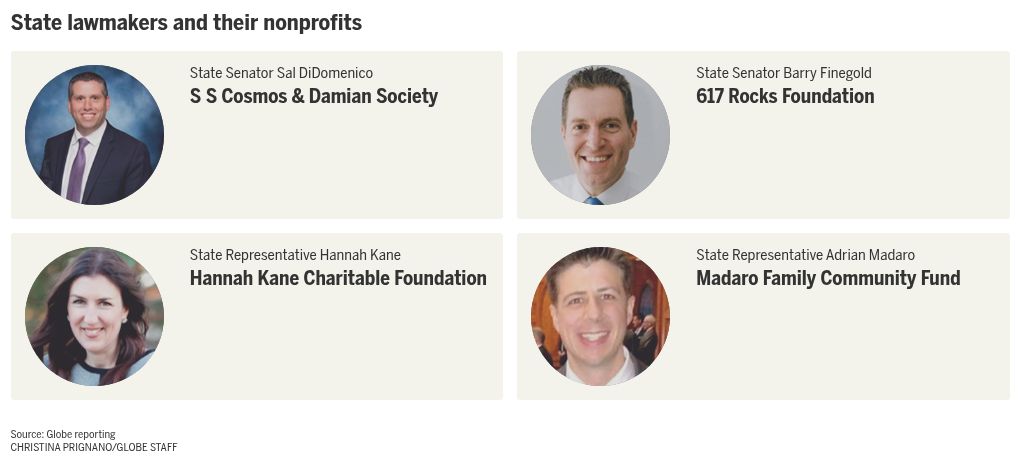

A Globe review of IRS 990 forms found that a handful of state lawmakers actively run their own nonprofits, which hold fund-raisers and events that solicit donations.

A developer building a massive housing project in East Boston, for example, donated to a nonprofit run by a state representative whose district encompasses the construction site.

“A donation like this is like a gift to the official and therefore should be disclosed,” said legal scholar Richard Briffault, a professor of legislation at Columbia Law School in New York City.

“The focus should be on things that are likely to lead to reciprocity and gratitude. If someone does something nice for you, there is a natural inclination to give it back,” said Briffault, who also served as chairman of the New York City Conflicts of Interest Board. “Unless there is a specific rule on this, it’s likely to slip through cracks.”

Because nonprofits are not required to disclose their donors, it’s also nearly impossible to know who is donating and how much. However, a review of websites and social media accounts for nonprofits run by state lawmakers provides a glimpse into the practice.

Take for instance, Representative Adrian Madaro’s “Madaro Family Community Fund,” which brought in $112,000 for its 2023 “Eastie’s Elves” holiday fund-raiser, a community toy drive backed by some notable names.

East Boston Neighborhood Health Center sponsored the fund-raiser with a $10,000 donation. A dozen lobbyists from three different firms donated to the fund-raiser and also chipped in maximum $200 donations to his political campaign.

Other $10,000 checks came from Amazon and HYM Investment Group, a real estate company that is building a 10,000-unit housing development at Suffolk Downs, which will be the single largest housing development in the region’s history when it’s done. The project is in Madaro’s district.

Others on the donor list included some of Boston’s top lobbying shops: Commonwealth Counsel; Serlin Haley; Smith, Costello, and Crawford; Travaglini, Scorzoni, & Kiley; and Rasky Partners. None responded to a request for comment.

One week after the Globe inquired about the nonprofit’s donors, Madaro filed an ethics disclosure with the House clerk to provide a list of donors and to “dispel the appearance of a conflict of interest.”

“A reasonable person could conclude that a person or organization could unduly enjoy my favor or improperly influence me when I perform my official duties, or that I am likely to act or fail to act as a result of kinship, rank, position or undue influence of a party or person,” he wrote in the disclosure.

Madaro, cochair of the Legislature’s revenue committee, continued: “I do not make decisions about potential legislation, my involvement in community matters or the provision of constituent services based on whether particular individuals or entities have, or have not, contributed to the Fund.”

In the disclosure, Madaro didn’t indicate taking any further action, and told the Globe “donations to our nonprofit have no bearing on policy decisions at the State House.”

This sort of giving is not allowed elsewhere.

At the federal level, members of Congress who maintain or control a nonprofit can’t solicit or accept monetary or in-kind contributions from lobbyists or foreign agents.

Under California’s transparency laws, an elected official who fund-raises or solicits donations to be given to another individual or organization must report payments over $5,000 to the agency where they hold office.

While those laws don’t exist at the state level in Massachusetts, the laws governing what candidates can accept and what they must disclose exist for a reason, said Delaney Marsco, director of ethics at the Campaign Legal Center, a Washington, D.C.-based watchdog.

“It’s an area that is ripe for corruption,” Marsco said. “By allowing a lobbyist or a contractor or an interested party to circumvent these approved channels and instead donate to nonprofits who do not have to disclose their donors . . . it takes away that transparency element and it allows lobbyists to do so in secret. That is very bad and a detriment to the public’s trust.”

It’s not just Madaro’s events that solicit such high-profile donors. State Senator Sal DiDomenico, the chamber’s assistant majority leader, hosts an annual Italian feast hosted each summer through the nonprofit S S Cosmos & Damian Society Inc.

Sponsors of the Everett Democrat’s 2024 event included pharmaceutical companies, real estate developers, and casinos with a presence in the state. The list also included a number of high-powered lobbying firms such as Dempsey Associates and Serlin Haley, whose lobbyists are bound by the state’s strict campaign finance law.

These firms did not respond to a request for comment.

To be sure, there are altruistic reasons to give to nonprofits.

DiDomenico said his family has been part of the Italian festival for more than 70 years, “long before I was ever thinking about elected office.”

“There is absolutely no connection or influence by anyone associated with this community event on my work in the Legislature,” he told the Globe in a statement. “This includes vendors, sponsors, attendees and society members.”

Senator Barry Finegold’s annual benefit concert for Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, a 5,000-seat fête held at MGM Music Hall in Boston’s Fenway neighborhood, had a similarly noteworthy list of sponsors.

Finegold, who chairs the Legislature’s economic development committee, has raised more than $500,000 for his charity over the last four years, the Globe has previously reported, thanks to sponsors such as Boston Beer Company, Arbella Insurance Foundation, Comcast, and First American Title — all of whom have registered lobbyists who have donated to the legislator-lawyer’s campaign account.

None responded to a request for comment.

In a statement, Finegold said his family has been hit hard by cancer, and that raising money for hospitals such as Dana-Farber “is especially critical this year with potential federal cuts.”

“We are committed more than ever to do everything we can to beat cancer,” he said.

Republican state Representative Hannah Kane’s nonprofit, “The Hannah Kane Charitable Foundation” hosts an annual charity golf tournament that draws big names such as Grossman Development Group, a major real estate developer.

Various banks, construction firms, and waste management companies sponsor the carts, caddies, birdies, and the barbeque lunch that follows.

The fund-raiser, which was started by former lieutenant governor Karyn Polito, sent $60,000 to three nonprofits in Shrewsbury and Westborough last year —Shrewsbury Youth and Family Services, St. Anne’s Human Services, and the Westborough Food Pantry.

“The impact of the generous tournament donors is on the three nonprofit human service organizations who serve hundreds of residents in Shrewsbury and Westborough,” Kane told the Globe. “The donors do not impact my legislative work.”

Matt Stout and Anjali Huynh of the Globe staff contributed to this report.

Samantha J. Gross can be reached at samantha.gross@globe.com. Follow her @samanthajgross.