- For more than 10 years, the Climate Investment Fund (CIF) has supported Indigenous peoples and local communities to protect their forests through its direct funding mechanism, known as the Dedicated Grant Mechanism (DGM).

- The DGM’s unique governance model is designed and managed by the Indigenous peoples and local communities themselves.

- So far, CIF has provided $70 million to the DGM through its Forest Investment Program (FIP) and an additional $40 million has been approved for its Nature, People and Climate (NPC) program.

- While the DGM has led to positive impacts, expansion to other countries has, in some cases, been difficult and sources said the mechanism takes time to set up and communities can still struggle with the technical language.

For more than 10 years, a funding model has quietly done what many others have struggled to do: Funnel nature and climate finance directly to Indigenous peoples and local communities.

The Dedicated Grant Mechanism (DGM) was created by the Climate Investment Fund (CIF) in 2010 to support Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ involvement in forest conservation and community-led nature-based solutions. This came after Indigenous beneficiaries of CIF programs demanded that a portion of the funds be granted directly to Indigenous peoples and local communities for projects they design and manage.

Since the start of this program, $70 million has been allocated to communities through CIF’s Forest Investment Program (FIP) and $40 million has been approved for its Nature, People and Climate (NPC) program. The model doesn’t only direct funding, say project managers, but also addresses key obstacles — like donor mistrust in giving money directly to communities and the lack of local capacity to manage funding portfolios effectively.

“It’s not traditionally the direction that [the multilateral development banks] go,” said Paul Hartman, the lead for CIF’s NPC Program, explaining why their direct funding model, as part of a multilateral climate financing mechanism, is so little known and passes under the radar. We’re also rarely in the spaces and meetings on territorial governance and community finance, so the news doesn’t spread, he told Mongabay.

For years, communities have been underrepresented when it comes to decision-making and the governance of funds, say researchers. Little funding reaches communities directly and instead passes through intermediaries, such as NGOs, consultancies and development banks. This has been a consistent source of contention within Indigenous rights organizations.

“With limited access to institutional support and resources, these communities are often excluded from decisions that most often directly relate to their lives and livelihoods,” said Trisha Mani, a senior project manager at the Centre for Sustainable Finance at the University of Cambridge’s Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), who is not affiliated with CIF. “The DGM model lays the foundation to correct this imbalance by delivering resources directly to the community level, supporting local climate action, biodiversity conservation, and livelihood restoration.”

According to an independent evaluation of the fund by consulting firm Indufor North America and ICF, the governance model is “innovative.”

“Once the governance and project management infrastructure was set up, the DGM proved to be efficient and mostly effective,” Jeffrey Hatcher, managing director of Indufor North America and author of the independent evaluation that was completed in 2024. “One of the key outcomes from the DGM experience has been that [Indigenous peoples and local community] organizations can manage climate finance even within complex administrative contexts like the World Bank and CIF.”

In one case, in Brazil’s Cerrado biome, traditional Geraizeiro communities affected by the expansion of eucalyptus monoculture plantations led to actions to improve water access, such as through the construction of water networks and recovery of springs, with the help of the DGM.

“In our region, we still have a problem with water, but it has been greatly alleviated with the support of the project which brought solutions that we still use today,” Fabricia Costa, a project implementer with the DGM and vice-president of COOCREARP, a local cooperative that focuses on the conservation of the Cerrado, told Mongabay over a video call.

While the DGM has led to positive impacts across the 12 countries where it has been implemented, expansion to other countries has, in some cases, been difficult as some governments have been reluctant to participate due to the lack of control they have over the finance, Hartman said. Sources Mongabay spoke to said the mechanism takes time to set up and some communities still struggle with the technical language.

To facilitate transformational change, say the authors of the independent evaluation, the DGM will have to focus more attention on actions to address systemic problems beyond the community level, such as the drivers of deforestation. If not, it could struggle to scale up and sustain the benefits it has produced.

How it works

The DGM receives money from two CIF programs: the FIP (focused on forest conservation projects) and the NCP (focused on people and climate projects). Under these programs, there are multiple projects across several countries, such as Brazil, Nepal, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). There is also a global project which focuses on gathering information and lessons from DGM projects across the world, in addition to knowledge exchange.

On the global level, representatives of a Global Steering Committee, which is mostly made up of Indigenous peoples and local community representatives, combine reports from the national projects, establish and strengthen networks and partnerships across organizations and ensure that the DGM representatives are present at international events, such as the U.N. climate conferences, or COPs.

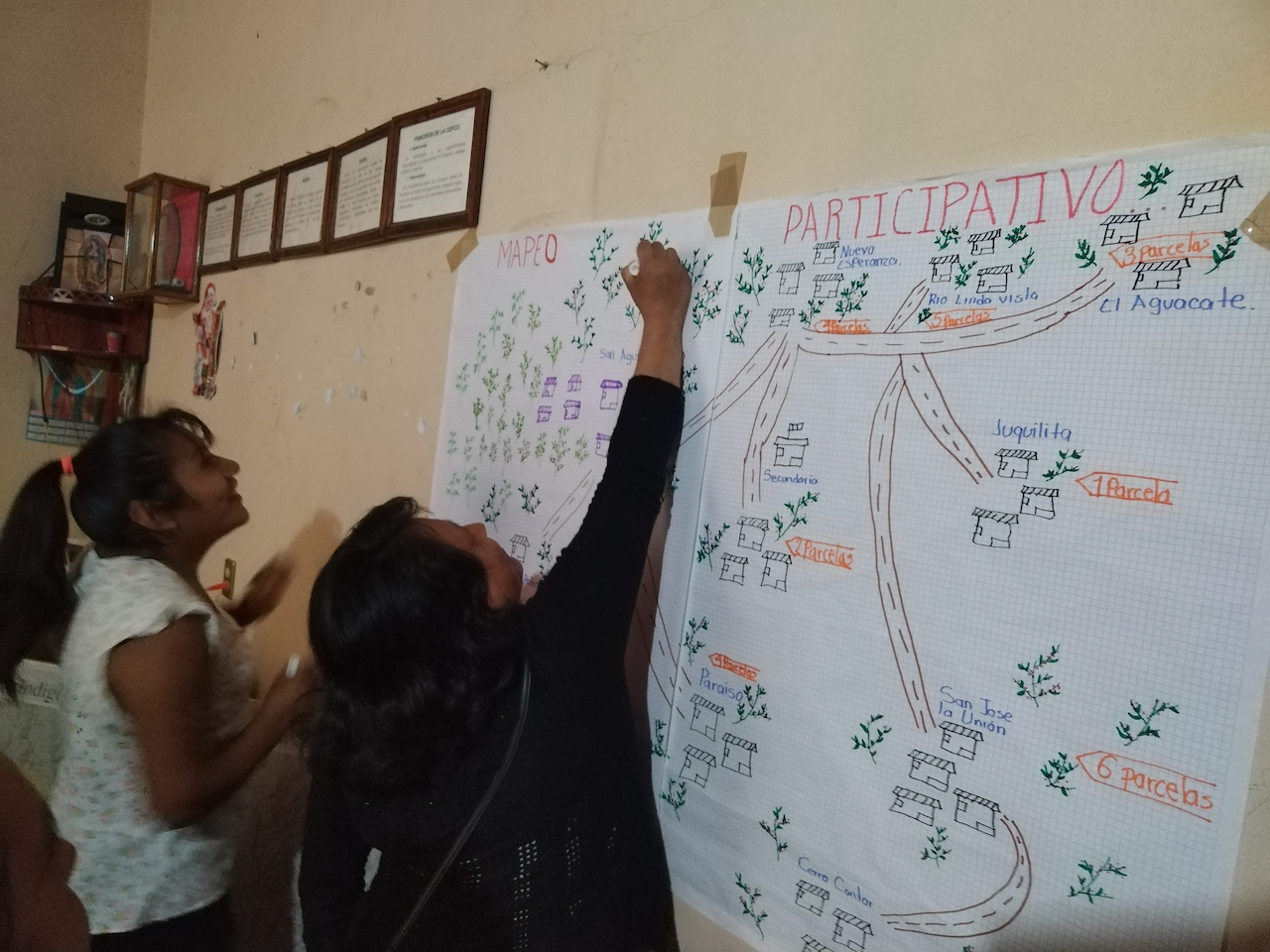

Indigenous peoples and local community representatives are also at the center of each project on a national level. They make up each country’s National Steering Committee (NSC), which make funding-related decisions, such as which community projects and communities to fund and how much money should be allocated to technical assistance and capacity building, as well as community-level execution and implementation. Meanwhile, the National Executing Agency (NEA), which is usually an NGO or research entity selected by the agency, acts as secretariat to the community representatives, disburses the chosen funds and then reports to the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs).

The NEA takes the responsibility for reporting to the banks away from communities who receive the money, like auditing and writing long technical reports, ultimately removing barriers and lack of trust and capacity issues that prevented communities from receiving funds directly. These mechanisms are also important for the international community to have trust in the system, so they know their funding is being used to achieve the results that they expect, Hartman explained.

MDBs, such as the World Bank, the International Finance Cooperation (IFC), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the African Development Bank (AfDB), also provide any needed support and capacity building.

Hartman said CIF has worked with the banks to build this infrastructure that creates a firewall between the decision-making of the community committees and all the fiduciary responsibilities and the monitoring of the dispute mechanism, “all the things that are required for there to be a robust program or project for those communities, to protect the communities, to ensure they have these mechanisms there, the safeguards in place.”

When they started, they never had any safeguards, said Martua Thomas Sirait, the director for Indonesia Operations and head of policy support at the Samdhana Institute, an organization that serves as the NEA for the DGM project in Indonesia. “But this [DGM] project required grievance and safeguard [mechanisms] so quickly we learned about this together with the bank,” she told Mongabay over a video call.

All of these components, from the NSC to the NEA, as well as the support of local governments and the MDBs, are in place to support the grantees who are in charge of the implementation of sub-projects and the preparation of reports for the NEA.

One of the sub-projects the DGM has supported in Indonesia is an initiative to secure land rights across Indigenous communities. In Mexico’s Oaxaca region, the DGM has helped communities improve their quality of life through organic coffee production.

“One very positive aspect of the project is that it involves producers from the beginning, listening to them and seeking strategies that fit their needs and the conditions of each community, since each community is different,” Rocío Aguilar Méndez, a DGM Indigenous Youth Fellow who works with over 250 Zapotecan Indigenous coffee agroforestry farmers, told Mongabay over a video call. “There was a great deal of flexibility. In addition, producers were trained and supported so they could plan, manage and implement the financial resources themselves.”

CIF also provides the communities with operational guidance and training — actions that support them beyond DGM-funded projects. But ultimately, decisions, such as what to fund, who to fund and where, is in the hands of the communities.

“I see that with this training, we can achieve much more,” Costa said. “This encourages us to also pursue the financing aspects and also not wait only on larger institutions. Community-based institutions also have to be independent, be able to write their own project [proposals] and raise their own resources and manage them.”

Challenges

While the DGM has led to successes around the world, the process has not always been straightforward, especially during the early days of set-up and operations.

As Hatcher pointed out, “working out the details to build processes and governance bodies took tremendous energy from rightsholders representatives, World Bank staff, CIF counterparts and in some places government counterparts.”

Sirait told Mongabay that during the preparation stage of the Indonesia DGM project, Samdhana found it difficult to follow some of the requirements of the bank and the team had to ask for adjustments to make the administration system simpler. In addition, because situations can change quickly on the ground, the administrative hurdles they must go through to obtain more support or budget from the DGM mean it sometimes isn’t available quickly enough.

“When it’s not in the budget or the plan, we need to ask for a revision of the plan and a No Objection Letter (NOC) [from the bank],” Sirait told Mongabay. “The speed of it can’t compete with the current dynamic of what’s happening on the ground.”

Instead, he said, a certain percentage, such as 10% of the total grant, could be put aside for responsive support. This means communities whose sub-projects have been affected by policy changes, the emergence of an agrarian conflict or leadership transitions, can have quicker access to funds in times of urgent need.

Another challenge the communities sometimes face is the technical language of the DGM. “The people who live in these communities are actually very smart, but sometimes technical teams don’t look for strategies to facilitate this capacity development so that we can truly communicate to the world what we are experiencing, our reality,” Aguilar said.

She added that despite those difficulties, all in all, the communities were listened to by the NEA from the very beginning of the project development process and extra support and adjustments have been made to refine the process.

“The model has already been adopted in several countries, demonstrating its potential across diverse contexts,” Mani said. “That said, scaling this approach, particularly with private finance, comes with some challenges. The localized nature of these projects can make it difficult to create standardized metrics, models and comparable data that commercial investors often seek.”

Hartman said the next step is to raise the profile of the program and, taking into consideration the lessons they have learned, replicate aspects of it. “The goal here is to make sure that it’s recognized as one of the models that exists, not the best model, not the only model, but it is a model that exists that could be utilized in those circumstances where it’s appropriate.”

Banner image: With support from the Dedicated Grant Mechanism, Indigenous Cibarani people from Indonesia secured an official customary forest designation, enabling them to improve their livelihoods. Image by the Climate Investment Fund (CIF).

Citations:

Indufor North America and ICF. (2024). Climate Investment Funds Midterm Evaluation of the Forest Investment Program. Retrieved from: https://www.cif.org/sites/cif_enc/files/resource-collection/material/midterm-evaluation-of-the-forest-investment-program_0.pdf

Sorsby, N., Holland, E., Waldron, A., Degawan, M., Karmushu, R., Spencer, R., Chowdury, M., Mwale, B., & Huber, C. (2025). Limited GEF finance for nature reaching the local level. Retrieved from: https://www.iied.org/22637iied

Indigenous representatives still excluded from COP30 decision-making, says leader

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.