Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In late November, a work of art called Comedian, by Maurizio Cattelan, sold at auction for just over six million dollars. Comedian is better known by its description: a banana duct-taped to a wall. The buyer was Justin Sun, a cryptocurrency entrepreneur and major investor in World Liberty Financial, Donald Trump’s digital-asset company. Two years ago, Sun had made headlines when he and his firm, Tron, which specializes in cryptocurrency- and blockchain-based entertainment, were charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission with fraud and other crimes. (The case was recently put on hold by the SEC, the Trump administration having eased up on the government’s pursuit of corruption.) Back home in Hong Kong, upon receiving Comedian and its certificate of authenticity, Sun held a press event. Onstage, he compared the piece to crypto—“the real value is the concept itself,” he said—and proceeded to eat the banana.

Callan Quinn—a thirty-year-old reporter for CoinDesk, one of the largest and most popular outlets dedicated to crypto news, covered the story. “As for what I was thinking, it was something along the lines of how ridiculous this all was,” she wrote. “But it’s meme coin season, and things with absolutely no intrinsic value are very in right now.” Her article described mixed reactions in the audience and Sun’s history of similar stunts. She said that Nick Baker, a deputy editor, was pleased with the piece. Once it was published, she expected some backlash from Sun’s camp, but didn’t hear anything. Then, a few days later, she got a call from Baker. “He’s apologizing,” she recalled. He told her that the article had been deleted.

Tron had complained to Bullish—CoinDesk’s parent company, which operates a cryptocurrency exchange platform, and for which Tron was set to sponsor an upcoming conference. Bullish then ordered that the piece be taken down. The editorial team pushed back, writing letters to management asserting CoinDesk’s editorial independence and asking that the article be reinstated. Bullish was not swayed. A few weeks later, the company let go of the top editorial staff: Baker, as well as Kevin Reynolds, the editor in chief, and Marc Hochstein, another deputy editor. (The chief executive of CoinDesk said at the time that it was a planned layoff, not a response to Quinn’s article or the staff’s defense of it; neither CoinDesk nor Bullish replied to my requests for comment.)

To many in the crypto news community, the episode represented a startling turn. CoinDesk, founded in 2013, had gained a reputation for hard-hitting reporting by breaking the story that led FTX to declare bankruptcy, and the site had produced courageous, sometimes unflattering coverage of its former owner, Digital Currency Group. Now, evidently, it was subject to the whims of crypto billionaires. Quinn decided to resign.

The story had wider reverberations, too, given Trump’s promise to usher in a new crypto age, and his move to place crypto-friendly officials on the SEC. Ahead of the inauguration, Tron unveiled a nonprofit organization, the Digital Sovereignty Alliance, which sponsored an “Inaugural Crypto Ball” in Trump’s honor, during which he introduced, on Truth Social, a $Trump meme coin. Most recently, the Trump Media and Technology Group announced that Truth Social would move into the financial services sector, offering investments tied to Bitcoin, and, within days, Trump signed executive orders that established a federal Bitcoin stockpile and suspended enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act; Tron has been, as the crypto-focused journalist Jacob Silverman wrote recently, “a favored money-laundering tool for global cybercrime.” Pam Bondi, the attorney general, issued an anti-corruption-fighting directive similar to Trump’s. As powerful media owners enact changes at mainstream outlets aligned with Trump’s priorities, CoinDesk looks increasingly to be a proof of concept, a newsroom that can be molded for purpose.

In trying to make sense of this moment—the departure from norms, the disruption to staid tradition, the grift—there seems to be much to learn from those who know how to cover crypto. As in any beat, it’s complex: CoinDesk is part of a self-contained crypto media-sphere, which tends to be inhabited by those who believe in the cause; reporters coming from outside, trained in old-school financial journalism, can miss the significance of in-jokes, or overestimate coin values, which are easy to manipulate. But a number of reporters, such as Quinn, have managed to become immersed in the world of crypto without being swallowed up by it—even if that’s just what those who control much of crypto media would like. When I spoke with Andrew R. Chow—a technology correspondent for Time and the author of Cryptomania (2024), about the FTX crash—he described the beat in terms that struck me as fitting for much of political journalism: “There are so many people selling so many stories,” he said. “They’re super charismatic and they can deliver these amazing narratives—and often, in crypto, there’s really nothing behind it at all. It’s often not until you get some hindsight that you realize which were the heroes and the villains. It makes it very hard to construct narratives in the moment.”

The modern blockchain appeared in 2009, following the Great Recession, and amid wide disillusionment with financial institutions. That year, the New York Times hired a reporter to focus on the beat. But by and large, mainstream publications didn’t start picking up the story until 2013, when Bitcoin hit a billion-dollar milestone. Crypto investors started inviting journalists to dinner parties, pitching them on the potential of the blockchain. Michael Casey, who is fifty-seven, and was then an economics reporter for the Wall Street Journal, was on the guest list. He’d spent years writing about cycles of financial collapse in Argentina, and the idea of a monetary system that didn’t depend on centralized institutions appealed to him. “I just found it absolutely fascinating,” he recalled. Casey started writing about crypto for the Journal and publishing books on cryptocurrency.

Coverage continued in fits and starts, following the volatile boom-and-bust cycles of crypto markets. Reporters approached the subject with a generally critical but curious eye, chronicling the momentum of startups, the first time someone used Bitcoin to order a pizza, and opinions such as “Bitcoin Is Evil.” By 2017, as crypto was booming, Casey joined CoinDesk, which had begun making a name for itself covering the industry from within. “We combined that classic newsroom structure and capacity with young, up-and-coming, tech-savvy, scrappy reporters who could do one thing that was so important—read a blockchain,” he said.

Around this time, more crypto-focused outlets debuted, including The Block and Decrypt, covering industry news, primarily for investors. (Decrypt also attempts to onboard curious normies with Decrypt U, featuring a glossary of blockchain-related terminology.) Many of the writers for these sites are stakeholders—as they cheerily disclose in author and editor bios—which sets them in contrast to reporters for mainstream newsrooms, which tend to prohibit individual holdings. (At the Journal, reporters can make use of a communal wallet for the purposes of research.) Casey invests, and sees no conflict-of-interest problem. “Blockchain technology is a net good for society,” he said. “It is in everybody’s interest that technology develops in the fairest, most open, transparent, and most available and well-regulated framework possible.” But Molly White—a researcher who examines crypto grift and influence in political campaigns and writes a newsletter featuring a weekly summary of crypto updates—told me that disclosures don’t do enough to relay the true incentives underlying crypto reporting. “Purely disclosing the tokens does not provide a terribly complete picture,” she said. “There are ways to have conflicts of interest in crypto that are not necessarily made evident by the tokens that you hold,” from NFTs to Polymarket bets.

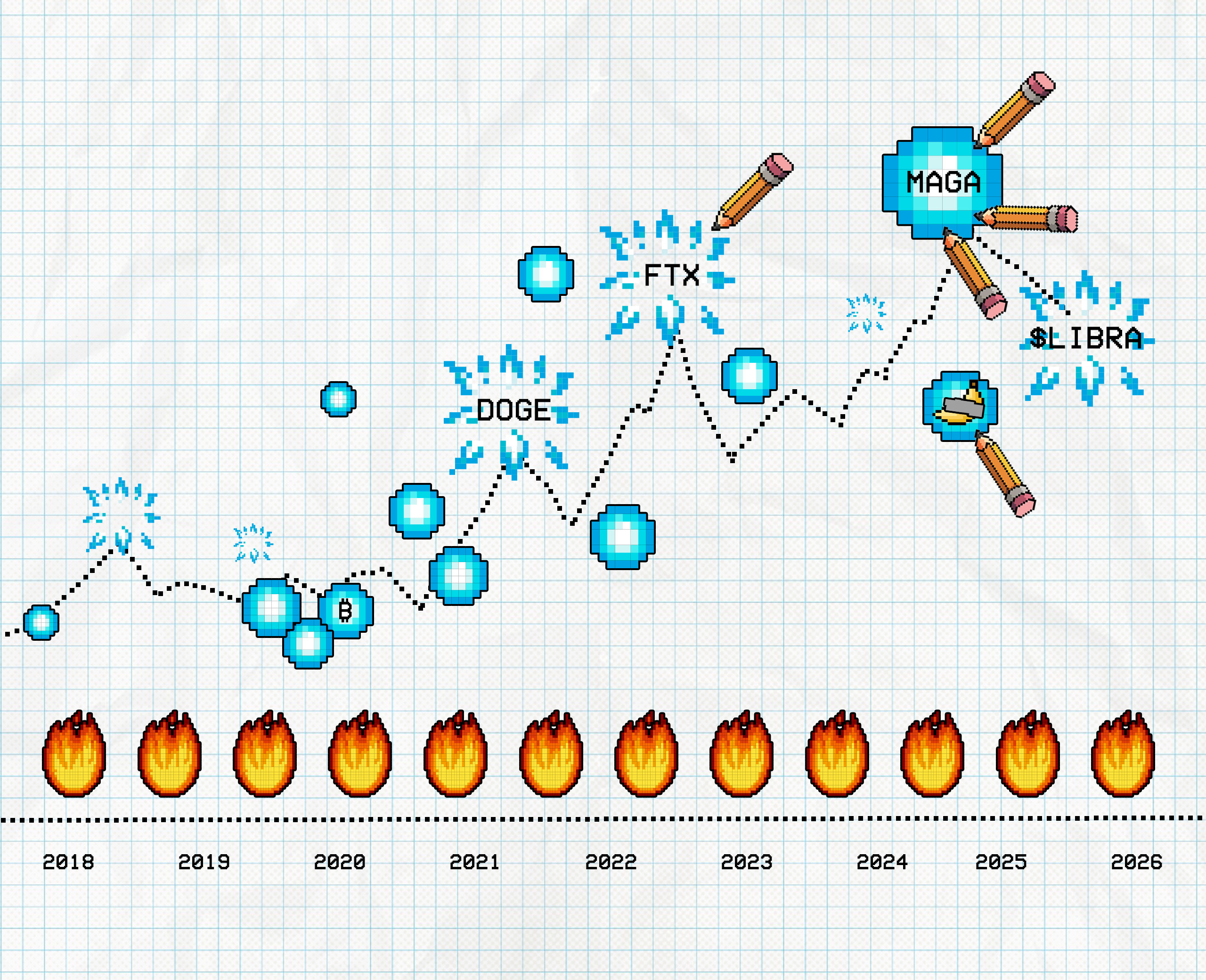

That has seemed not to bother the true crypto-heads, however, for whom the most trusted sources of crypto news emerged from—typically anonymous—handles on Twitter and Reddit—ideal places to keep track of developing memes, and which embodied the decentralization ethos. But in 2018, just as the environment for crypto news was filling out, the market suddenly collapsed. For those invested, the fall was worse than the dot-com crash. CoinDesk survived—in part by earning trust from its rigorous reporting and deep understanding of the beat. Even so, like many crypto publications, CoinDesk relied on a fairly small and powerful pool of industry sponsors. “I think that’s what condemned us,” Casey said.

Another crash, in 2022—brought on, in part, because of CoinDesk’s breakout reporting on FTX—forced Digital Currency Group to sell. Bullish bought the site the following year, for close to seventy-five million dollars. At the time, Tom Farley, the CEO of Bullish, promised that CoinDesk would maintain journalistic independence. Casey left to work on his own venture; Quinn joined soon after that. Sam Bankman-Fried, the founder of FTX, went to trial, and crypto came in the sights of financial journalists everywhere. “The joke that people always tell me about crypto is that it’s like a century and a half of financial history squeezed into sixteen years of actual history,” David Yaffe-Bellany, who has been covering crypto for the Times since 2022, said.

In 2023, Silverman and Ben McKenzie (yes, the former OC star) published Easy Money, scrutinizing the crypto market as terrain for speculation and fraud. The more crypto came to penetrate the wider culture, the more stories of grift emerged. McKenzie came to view investors as being either “believers or gamblers”—and his writing, he told me, has been for the 90 percent of people “who haven’t been brainwashed.” That means, though, that a serious journalist covering crypto may come up against hard limitations of impact. As McKenzie put it, “I don’t believe you can convince a gambler to stop gambling with facts.”

When Trump minted the $TRUMP meme coin, many reporters strained to understand what was really going on. News outlets’ initial estimates of the coin’s value varied wildly, ranging from twenty to seventy billion dollars. “Perhaps that should have been a sign to these reporters that the numbers aren’t real,” White wrote in a newsletter. “Fully diluted valuation is an estimate so flawed that even publishing it should be considered journalistic malpractice.” Soon came the $MELANIA coin. The value of $TRUMP plunged. White analyzed the damage for the Times: 810,000 wallets fell victim to the price drop. More than 80 percent of the coins were owned by Trump.

After that, some crypto investors turned on him. Chow noted that many in the MAGA crowd have flocked to crypto, but not the other way around, and plenty of coin-holders are Trump skeptics. “I think there are a lot of crypto folks who were once cheering him on who have gotten more and more ambivalent or disillusioned with his extractive approach,” Chow said. “The moment that it all started going to shit was when the Melania coin dropped.”

Grasping the how and why of this mini-saga requires technical and cultural understanding as well as experience with financial reporting. The blockchain makes crypto appear to be transparent—but visibility, alone, does not always reveal the whole truth. Trades are made by pseudonymous investors, and the chain is so extensive, with so much data, that it can be incredibly difficult to know where to look; the market is a world unto itself. Even a hack can take weeks to notice, as in the case of 2022, when a North Korean group, Lazarus, hacked Axie Infinity, a blockchain video game. “Nobody was paying attention,” Chow said.

Beyond that, much happens “off chain”—including most of the problems that were associated with the FTX case. “Most stuff in crypto doesn’t really seem to happen on chain, if you’re talking about, like, political influence and deals and stuff like that,” Quinn said. On social media, “you’ve got to pay attention to these anonymous accounts with little cartoon avatars that have, like, half a million followers and therefore can say influential things,” Yaffe-Bellany told me. White often sees journalists quote crypto-focused accounts uncritically even when those accounts are, as she put it, just “taking the piss.” Jokes and memes are their own language, in which a crypto reporter must be conversant. “They’re very dry humor or it’s a very inside joke, and then get taken at face value,” she said.

In the age of the blockchain, old-school reporting techniques still apply: face-to-face is best. Quinn found that to be the case in Hong Kong. “I understand having anonymous sources,” she said. “But when you’re responsible for a company worth millions, I think people should know your name.”

It’s also crucial to be mindful of coverage as hype—as with vitriol or falsehoods that emanate from MAGA-land, providing a platform comes with risks, and even critical discourse can be exploited. “I sometimes worry that by covering certain things, you’re kind of giving more attention to these meme tokens that will result in more people investing in them and the price going up,” Quinn said. “There’s so many influences in the information that’s put out by these companies trying to get people to invest, and it’s just nonsense.”

That will only become easier as the SEC, under Trump, sets about dismantling its crypto investigations unit and halting legal action against exchanges such as Coinbase, Binance, and Kraken, loosening restrictions. “Crypto feels very emboldened to build right now, without being prosecuted,” Chow said. And yet, without oversight, more of “trad fi” (traditional finance, in crypto parlance) is set to feel the impact when the next crash comes. Such was the case recently in Argentina, where President Javier Milei promoted, in an X post that he shortly deleted, a cryptocurrency called $LIBRA, whose value rapidly skyrocketed and then collapsed—a classic “rug pull” (a crypto term for abandoning a project after raising funds, leaving participants with worthless tokens) that rattled the nation’s economy; Milei is now under investigation for fraud. Many Argentinians invest in cryptocurrency—which, in light of extreme inflation, they commonly view as safer than the peso. Comparisons to the United States, in the wake of Trump’s commitment to Bitcoin, abound.

That story was covered by CoinDesk, including reactions from Bitcoin-adjacent executives—at least some of whom were underwhelmed. (Absent a buying plan, the founder of a crypto hedge fund posted on X, the strategy was “a pig in lipstick.”) Quinn and her ex-CoinDesk colleagues looked on as major outlets picked up on the reporting, much as they have on other crypto news; the drama of their exit seems not to have made a lasting impact. “This community has a five-second memory,” she said. “There are cases of scammers that rug-pull, then a year later they are considered rehabilitated. People forgive very quickly, it seems—or forget.” Her editors are now looking for work. She has followed this and other stories for her new Substack, Scamurai, focused on crypto scams. White welcomes the addition of an independent journalist to the scene. But as she told me, “It’s not lucrative to be a crypto skeptic.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.