The bank’s response to the backlash was swift: it tempered the quantum of the hike to 50%, setting it at a considerably lower ₹15,000. The quick damage control was probably sufficient to soothe customer outrage.

However, it would be wrong to view the move as “loot, thuggery of the middle class”, as alleged by some netizens. Rather, it should be seen as the bank’s response to structural shifts in the banking sector. There are winds of change blowing through the financial system, and as banks adapt to these changes, more such actions can be expected in future.

In a July 2024 speech delivered in Mumbai, then Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Shaktikanta Das described the financial landscape in India as going through a structural transformation, driven by two broad factors: technology and changing patterns of savings and investment.

Technology meets Gen Z

Technological advances have led to rapid growth in digital banking and created customer expectations of frictionless transactions. The result is that Indian banks have invested heavily in digital systems to retain customers, especially younger ones. At the same time, fintech companies have set up platforms where customers can save, borrow, invest or spend easily, all with a few mouse clicks. Fintechs do all that banks can, and more. Not surprisingly, an increasing number of Gen Zs prefer the click-and-connect model of fintechs over traditional banking systems.

View Full Image

Evidence of age skew in banking is quite stark. RBI data shows that 76% of individual deposits across banks were held by those aged 40 years or older. A decade ago, households invested mainly in fixed deposits and insurance. Today, mobile banking and investing apps have enabled a huge flow of retail money into all kinds of assets, including mutual funds, bonds, equity and even complex derivatives.

The diversion of household savings into non-bank channels means that banks can no longer rely on households as a captive source of funds, and households do not consider banks as the sole, or even major avenue, for savings. The result of this decoupling is that an important source of cheap funds—namely, household deposits—can no longer be taken for granted.

It has, in fact, started drying up. In 2023-24, bank deposits grew by a robust 12-13% year-on-year. By May 2025, deposit growth had slowed to 9.9%. The situation was worse for private sector banks. Between 2020-21 and 2023-24, the rate of deposit accretion by private sector banks soared, peaking at 20.1% in March 2024, before slumping to 12% in March 2025. In contrast, the rate of deposit growth for public sector banks was relatively more stable, at around 8-9% throughout these years.

The diversion of household savings into non-bank channels means that banks can no longer rely on households as a captive source of funds, and households do not consider banks as the sole avenue for savings.

In parallel, private banks were building up a huge personal loan book, as they raced to fund the massive post-pandemic pick up in borrowing and spending. By March 2023, personal loans accounted for nearly one-third of their outstanding bank credit. Specifically, the RBI was alarmed by their rising exposure to unsecured loans. In March 2023, 27% of advances made by private sector banks and 22% of those made by public sector banks were unsecured loans.

In November 2023, concerned about a potential bubble in unsecured lending, and the possibility of rising defaults in these loans, the RBI clamped down on unsecured loans and loans to non-banking finance companies (NBFCs). Credit growth slowed immediately, falling from 19% in 2023-24 to 11% in 2024-25 across all scheduled commercial banks.

Cost pressure

This cycle of rapid credit expansion followed by a slowdown, against a background of sluggish deposit growth, contains important lessons. The maths on deposits is simple: current and savings accounts (Casa) deposits are the cheapest, followed by term deposits, with non-deposit borrowings being the most expensive.

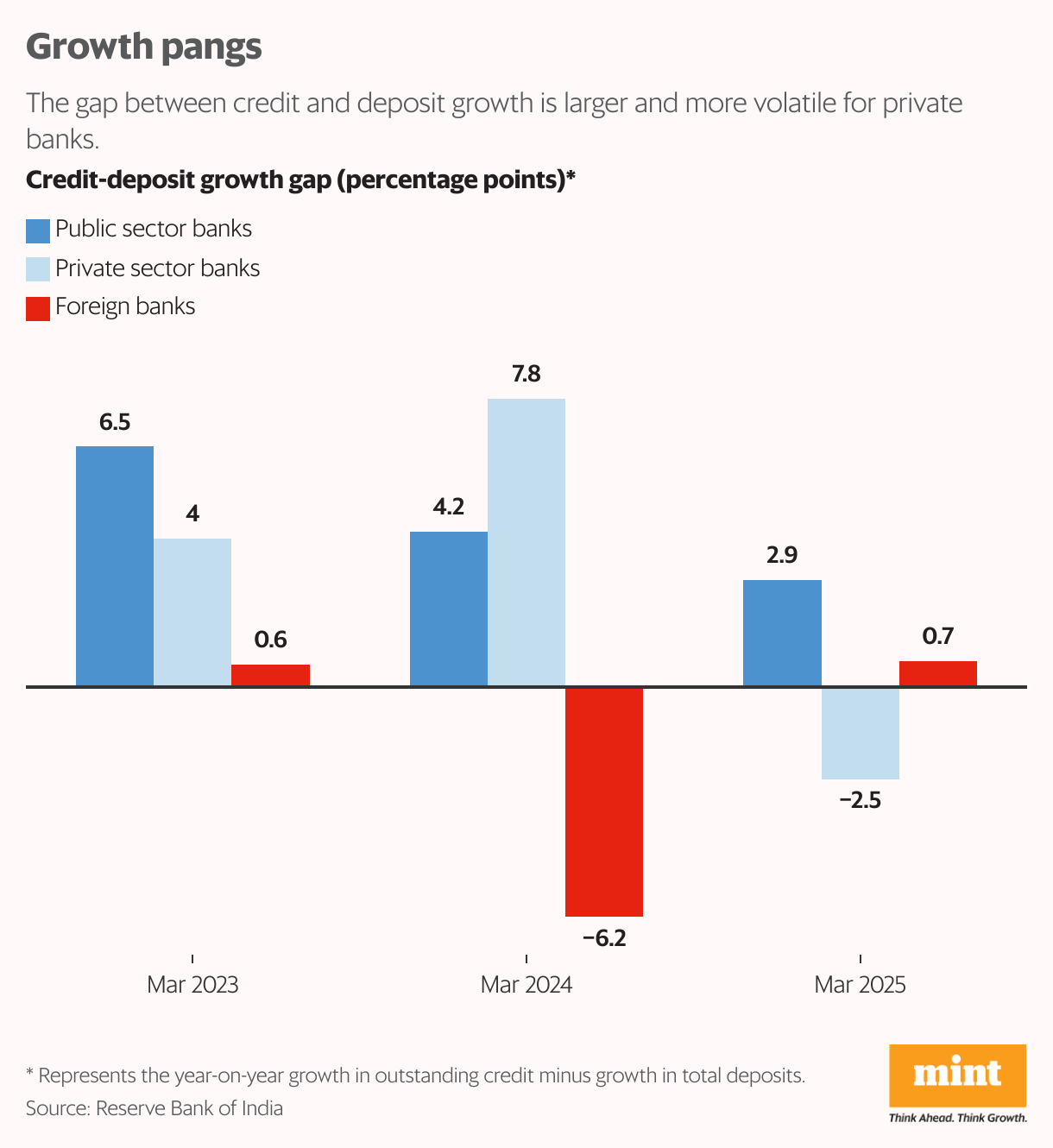

In 2022-23 and 2023-24, banks were lending so aggressively that credit growth outstripped deposit growth. Since interest rates were rising at that time, depositors shifted savings from Casa to higher-yielding term deposits. Banks were forced to compete for term deposits, or borrow from other sources, to compensate for tepid deposit growth.

Private sector banks faced a double whammy: on the liabilities side, their balance sheets had a lower share of deposits and a higher share of borrowing as compared to public sector banks. On the assets side, their credit was growing at a faster rate. The result was that private banks ended up with a significantly higher cost of funds.

By 2024-25, private sector banks braked so hard on lending that the credit-deposit imbalance inverted—credit grew slower than deposits. However, a credit slowdown of this magnitude is likely to be a blip, rather than a long-term trend. According to the latest RBI survey of professional forecasters (August 2025), bank credit is expected to grow 11% in 2025-26.

Already, results for the first quarter of 2025-26 show that loan books of leading banks are growing at a reasonable pace. In this April to June 2025 period, y-o-y growth in domestic advances for ICICI was 12%, SBI was at 11.1%, Bank of Baroda at 12.4%, Kotak at 13% and HDFC at 8.3%. Going forward, banks should be looking for ways to boost deposits, preferably of the low-cost Casa variety.

Deposit profiles

In this environment, why would a bank like ICICI voluntarily take the risk of excluding some depositors?

Two reasons stand out. First, the era of passively waiting for deposits inflows is over. Banks need smart strategies to attract deposits. For this, banks have to play to their core strengths in terms of type, size and location of deposits.

View Full Image

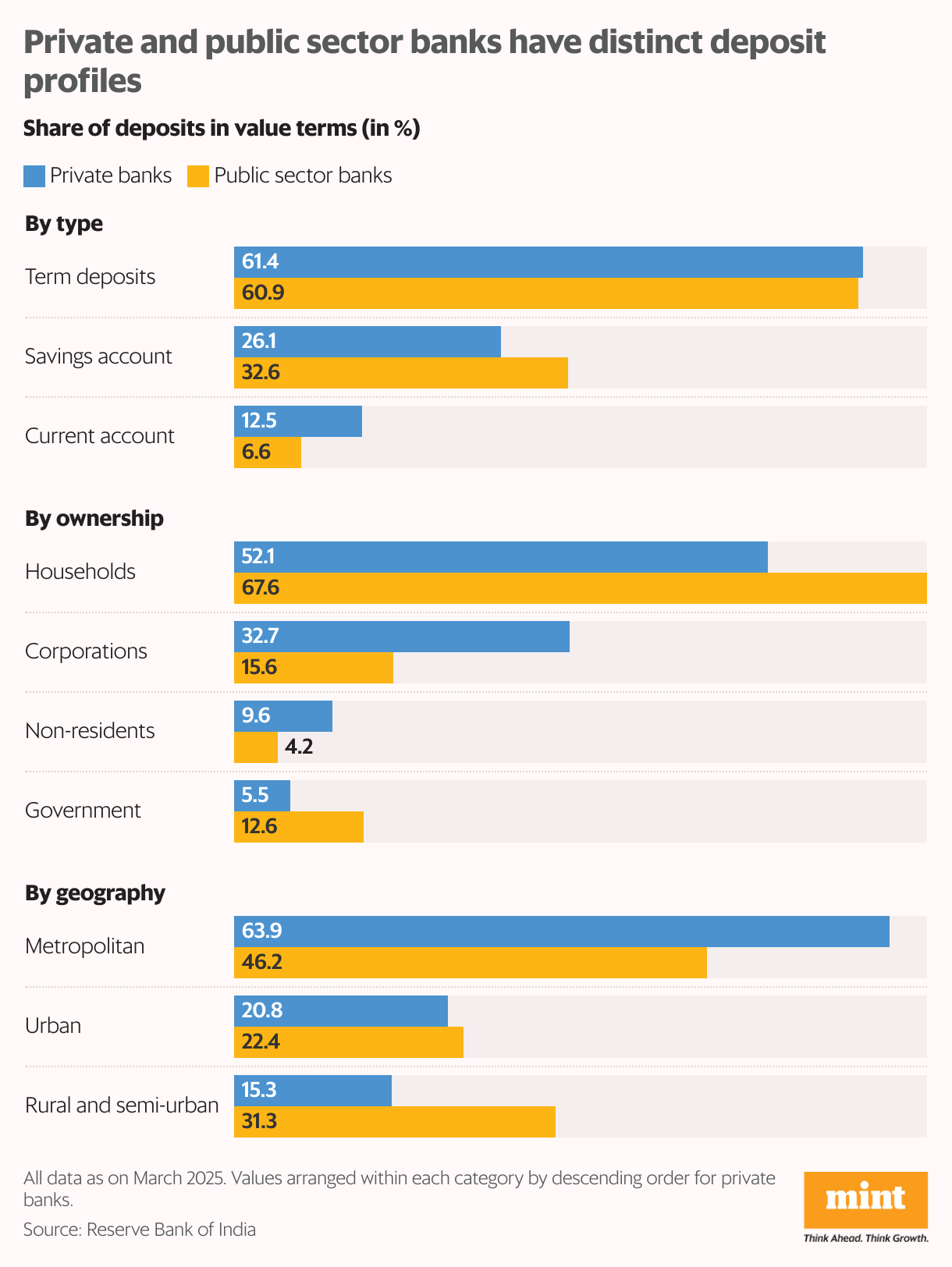

There are distinct differences in deposit profiles at a bank group level. In March 2025, about 32.7% of private bank deposits were from the corporate sector and another 9.6% from non-resident Indians—or, a total of 42.3%. The comparable figure for public sector banks was 19.8%. In contrast, 67.6% of deposits in public sector banks were from the household sector, against 52.1% for private banks.

The average ticket size of a private bank deposit (savings and term) was ₹1.7 lakh in March 2025, as against ₹80,000 for public sector banks. There is also a clear geographic disparity in deposits. For private banks, 60% of their deposits by number and a whopping 85% by value are from urban and metropolitan areas. Public sector banks have more deposits from rural and semi-urban areas.

These data points are enough to build a broad profile. Deposits of private sector banks are concentrated in big cities, and dominated by relatively large-value corporate deposits. To put it simply, the strength of a private sector bank lies in focusing on a small number of large deposits; while a public sector bank is more likely to attract a large number of small deposits.

This difference informs their business strategies. In 2020, public sector bank State Bank of India (SBI) waived the minimum balance requirement (MAB) on savings accounts; a few other public sector banks followed in later years. This inclusive strategy has allowed public sector banks to mobilize low-ticket deposits across the country.

By comparison, a private sector leader like ICICI is better off by raising its MAB, so that it can mobilize more funds per account. This strategy is akin to positioning itself as a ‘premium’ bank. By excluding existing account holders from the higher MAB norm, and by applying it to only new account holders, ICICI Bank was testing the waters.

Both strategies have their pros and cons. On the one hand, servicing a large number of deposits has a cost, but the advantage is that household deposits are typically sticky and less likely to leave the bank. On the other hand, having fewer accounts to manage is cost-effective, but comes with an added flight risk. In picking a deposit strategy, banks will have to trade-off between stability and cost-saving.

Banks will do what it takes to improve profitability. Bank net interest margins (NIM) declined in the April to June 2025 quarter, mainly because of a drop in lending rates. Private banks are hit much harder by a rate easing cycle, as about 87% of their floating rate loans are linked to the external benchmark lending rate (EBLR).

ICICI’s strategy was akin to positioning itself as a ‘premium’ bank. By applying a higher minimum balance requirement to new account holders, the bank was testing the waters.

Banks have two options to protect margins: reduce cost of funds or lend to riskier clients at higher rates. ICICI chose the first option by raising the minimum balance on savings accounts, which has the effect of increasing the share of low-cost Casa in its deposits. Recently, SBI and a few other public sector banks chose the second option when they raised the spread on home loan rates, thereby signalling their willingness to lend to weaker borrowers. These actions appear contradictory to the idea of financial inclusion, or of taking banking to the vast underserved masses. But the reality is that financial inclusion is a country-level aspiration; at an institutional-level, each bank has to adapt its business to optimize its profits, in a manner that aligns with its inherent strengths.

Bank-fintech handshake

As digitisation disrupts banking systems and customer behaviour, more such business decisions to implement ‘selective inclusion’ are likely to take place. These should be seen as responses to a third round of structural transformation in the banking sector.

View Full Image

The first round started in 1993, when banking licenses were granted to the private sector. The second round, initiated in 2015, aimed to clean up bank balance sheets. Today, as banks evolve from being standalone brick-and-mortar institutions to physical-cum-digital service channels, they will need to seamlessly integrate with the overall digital financial infrastructure. This will call for greater bank-fintech collaboration, so that banks can ride on the technological capabilities of fintechs to deliver a better banking experience.

In August 2024, S.S. Mundra, an ex-deputy governor of RBI, had described partnerships between banks and fintechs as a win-win proposition, as it enables data harnessing for inclusion and innovation. Already, leading banks have tied up with fintechs to improve delivery in verticals such as loan process automation, payment innovations, or customer service. More partnerships can be expected in the future.

How a bank adapts and differentiates itself from its competitors will depend on its asset-liability profile and customer orientation. For example, Bandhan Bank has collaborated with Salesforce to improve processing of home and corporate loans, which accounts for almost half its assets. ICICI bank has tied up with PhonePe to offer instant UPI-based credit to its pre-approved customers on the Phone Pe app. SBI has collaborated with M2P Fintech to offer innovative prepaid solutions across various use cases.

At its core, banking is about channelling funds from savers to borrowers, and this principle is not about to change. But there will be major shifts in intermediation channels and service expectations of savers and borrowers. In future, some banks may be fully-digital, others may work with cryptocurrency or accept stablecoin deposits. As traditional models become obsolete, the only solution for banks is to fine tune their business models to adapt to these changes.

howindialives.com is a search engine for public data.

Key Takeaways

- ICICI Bank’s recent move, to raise the minimum balance requirement for new savings accounts, faced considerable backlash.

- The action appeared contradictory to the idea of financial inclusion.

- As a damage control measure, it later lowered the hike.

- The move should be viewed as a response to structural shifts in Indian banking.

- Two factors are driving this transformation—technology and changing patterns of savings and investment.

- ICICI’s strategy was akin to positioning itself as a ‘premium’ bank.

- By applying a higher minimum balance requirement to new account holders, the bank was testing the waters.

- Financial inclusion is a country-level aspiration; at an institutional-level, each bank has to adapt its business to optimize its profits.

- Banks have two options to protect margins: reduce cost of funds or lend to riskier clients at higher rates. ICICI chose the first option by raising the minimum balance on savings accounts.

- This has the effect of increasing the share of low-cost Casa in its deposits.