Student mentors and past participants in the College Assistance Migrant Program, or CAMP, pose in 2021 at Portland Community College. From left, Fatima Sanchez, Joceyn Tapia, Nejdet De Jesus, Alejandra Villanueva, Eulalia Francisco and Sam Gonzalez. (Photo courtesy of Portland Community College)

The journey to and through college for Marisela Marquez Alonso and her three brothers began at Portland Community College, in a 50-year-old, federally funded program that now hangs in limbo.

The four siblings, who mostly grew up in Hillsboro, are the children of migrant farmworkers from Mexico who worked seasonal harvests in Oregon, California and Washington, and the first in their family to attend college.

To do so, they each relied on the federal College Assistance Migrant Program, or CAMP, to help pay for their first year at Portland Community College’s Rock Creek Campus and to counsel them and help them navigate through their freshman year. They’re among thousands of migrant workers and families who benefited from the program over the past five decades, but current students risk losing the college aid because the Trump administration withheld funds.

Marquez Alonso, who today holds an undergraduate degree from Oregon State University and a graduate degree in education leadership from Portland State University, said her family is “the definition of why the CAMP program works.” Along with financial aid, the program provides specialized tutors, academic advisers and career counseling.

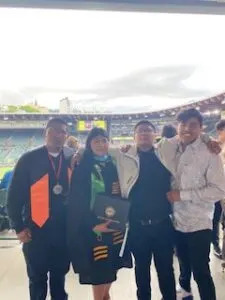

Marisela Marquez Alonso and her brothers at her graduation ceremony at Portland State University in 2022. (Photo courtesy of Marisela Marquez Alonso).

“One (brother) got his degree in business administration and he’s now working for Nike. The other one is a drug and alcohol abuse counselor. I mean, these are careers, professions, that my parents are far away from,” she said.

Thousands of migrant farm workers and their families have attended and graduated from college with help from the program, which former President Lyndon B. Johnson and his Office of Economic Opportunity established in 1967 as part of the “War on Poverty.” Johnson also oversaw the creation of the federal Migrant Education Program in 1966, providing K-12 schools with resources to keep the children of migrant farmworkers in school while on the move, and the High School Equivalency Program, or HEP, in 1967, to help migratory and seasonal farmworkers and their family members earn the equivalent of a high school diploma.

But in July officials at the U.S. Department of Education told the roughly 100 institutions of higher education across the country that offer those programs — including nearly all of Oregon’s community colleges and Oregon State University — that they will not receive $52 million in congressionally allocated funding until the federal education agency and the Office of Management and Budget undertake a “programmatic review.”

The federal officials offered no timeline for when they will end their review and release funds. President Donald Trump proposed eliminating all funding for the Office of Migrant Education in his 2026 budget as part of his broader dismantling of the federal Department of Education.

Officials at both the education and budget agencies did not respond to requests for more information or comments.

Two paths

Greg Contreras, director of the CAMP and HEP programs at Portland Community College and the president of The National HEP/CAMP Association, said federal officials are withholding $474,000 that the college expected to receive in July to run the programs next year.

In September, he will have 45 students starting in the College Assistance Migrant Program who might not get scholarship money they expected through the program, or many of the specialized services that students before them received. Across the country, more than 8,000 students were slated to be served by the HEP and CAMP programs, according to the association.

“We’re going to have a CAMP orientation in early September, where we’ll share with students two pathways to success: One, if we get our funds, the different services that they’re going to get,” he said. “The other pathway to success that we want to share with our incoming group of students is if we don’t get our funds, what the college can provide for them in the event that we don’t have a CAMP program.”

Contreras said federal education officials have given him no information about the fate of funding for the programs. Portland Community College has secured other funding for his job until Oct. 8, he said.

There are roughly 58 students enrolled in Portland Community College’s High School Equivalency Program each year, he said. Among the current students is Marquez Alonso’s mother, who could be left in limbo if the program is cut.

“She will have to find a different kind of GED program,” Marquez Alonso said. Her father, a recent graduate of the HEP program, just got his diploma in the mail.

Federal uncertainty around the migrant education programs has also made a mark on Marquez Alonso’s trajectory. She returned to Portland Community College two years ago to work as an adviser for the CAMP program there. But she recently took a different academic advising job at the college that’s not tied to federal funding.

“I am in no position not to have a job,” she said. “I was like, ‘I have to secure something.’”

She said she is unlikely to return to advising for the CAMP program, even if funding comes through.

“I don’t think financially it would be ideal,” she said.

SUBSCRIBE: GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX