India has an estimated 18 crore low-literate people who struggle to read and write even in their native languages. With smartphone penetration crossing 650 million and regional content consumption skyrocketing, banks, startups, and government organisations are racing to bridge this divide by leveraging voice-based technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Earlier, we would pay EMIs in cash. I wasn’t comfortable using mobile apps. Now, our entire loan process happened on the app. I didn’t have to visit the branch even once.

The central government recognises the gap as well. The New India Literacy Programme (NILP), launched in March 2023, aims to target five crore non-literate individuals aged 15 and above. With a budget of Rs 1,037.9 crore, NILP mobilises volunteers across India to conduct foundational literacy and numeracy training. Financial literacy is one of the scheme’s key components.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has also issued guidelines for setting up Financial Literacy Centres (FLCs) by leading banks. A public awareness campaign, titled ‘RBI Kehta Hai’, promotes financial literacy through multiple mediums and in various languages.

But voice has trumped vernacular.

“We were wrong in our assumption that a regular vernacular app [text-based in regional languages] will work for the aspirational middle class,” said Diptarag Deb, senior vice president of Ujjivan, speaking to ThePrint. “We went back to the field and asked people how they were using their smartphones.”

To conduct research and build the app, Ujjivan partnered with Navana.ai, a Mumbai-based company that develops multilingual voice AI solutions to make digital services more accessible for non-English speakers.

Deb and his team found that their target audience – primarily informal sector workers – were most comfortable with video, image, and audio content. Apps like YouTube and WhatsApp were among their most used platforms.

“Nobody types out messages in these communities,” said Deb, adding that sending voice notes was the dominant mode of communication. This led Ujjivan to combine vernacular languages with voice-based technology and launch their app in 2022.

The Indian government has also recognised the need to overcome language barriers, launching an AI-based translation platform under the National Language Translation Mission.

Launched in August 2022, Bhashini enables real-time translation across 11 regional languages, including Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, Kannada, and Bengali. The platform is being leveraged in the financial sector for voice-based UPI payments. By calling a dedicated number, even from a feature phone, users can transfer money by speaking in Hindi, English, or Telugu.

As the technology advances, operators say it’s only a matter of time before full-fledged, natural conversations in regional languages are fully integrated across all banking channels.

Also read: 35% bank accounts are inactive. Financial inclusion isn’t going to happen without women

Vernacular meets voice tech

The Ujjivan branch in Vigyan Vihar is bustling with young, female customers—most working in the informal sector through stitching, cooking or cleaning jobs. For many, it’s their first time interacting with a formal banking system.

Some clutch a yellow sheet of paper, recognised by customers as the loan statement. While digital adoption remains low, the bank is trying to get more customers online. Ujjivan primarily provides microfinance to groups of women and later disburses individual loans to those with exemplary repayment track record.

“When we started working on the problem [of banking access to customers with low literacy rates], we knew the solution had to be image-based, text-independent, and voice-dependent,” said Raoul Nanavati, co-founder and CEO of Navana.ai.

In 2019, brothers Raoul and Jai Nanavati set out to make digital services accessible to the next billion users—long before AI entered mainstream conversations. While pursuing their MBAs at Cornell Tech in New York City, the two co-founded Navana.ai, focusing on developing foundational speech models for all major Indian languages – work that led to the current version of the Hello Ujjivan app.

On the app’s menu tab, the yellow-coloured paper has been recreated as an icon, giving customers visual recall when checking their loan statements. Similarly, the icon for EMI payment shows a woman handing over cash to a loan officer. A hand placing a Rs 100 note in a brown matka (pot) represents a fixed deposit.

Each image is paired with a speaker icon, allowing customers to listen to the feature in the language they selected at the start. The app currently supports nine languages.

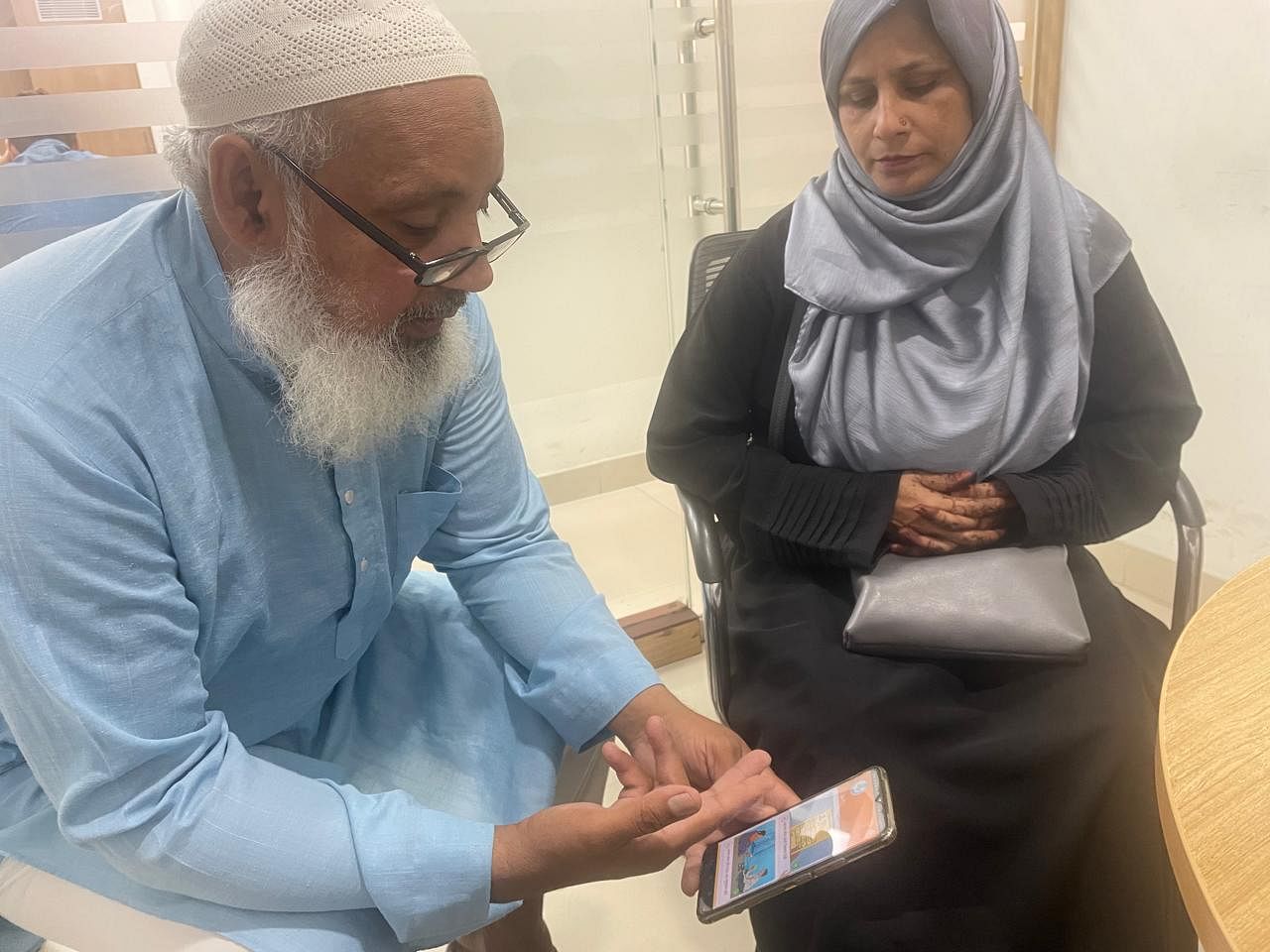

“I have an account with State Bank of India, but I don’t use it much,” said Sandeep, 41, who works in the pantry of a cybercrime unit in Delhi. His wife also took a group loan from Ujjivan, but he handles the repayments. “I can’t understand the app well, even if I choose Hindi as the language.”

Sandeep taps on the newly launched voice-bot feature next to the menu tab. The bot, developed by Navana.ai, allows customers to speak into the app. It comprehends their requests and guides them to the relevant page.

“Mujhe EMI bharna hai (I want to pay my EMI),” says Sandeep into the app. When the EMI payment screen pops up, he smiles, proud of how easily he navigates the platform. The technology recognises diverse Indian accents and pronunciations.

The combination of voice and visual cues seems to be working. Customers now log into the app one to two times a month, compared to once every six months – a significant improvement for this user base.

“Our end goal is conversational-based banking,” said Deb, referring to customers eventually being able to open accounts, pay EMIs, and make investments through natural language conversations with AI-powered bots.

Also read: Bihar’s new Hindu Sherni just got out of jail. Hindutva gets louder, younger

The Bhashini Push

Bhashini has made headway by enabling voice-based UPI transactions in collaboration with the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI). The entire process happens through voice commands.

“We imagined a person coming from a village and perhaps earning Rs100-200 per day,” said Amitabh Nag, CEO of Digital India Bhashini Division. “Now he wants to transfer it back to his family.”

According to Nag, the user simply calls a dedicated number and speaks in his local language. Currently, the service supports Hindi, English, and Telugu. The goal is to first cover 10 Indian languages, then expand to 22.

“He goes through this entire transaction using voice,” said Nag, adding that only the pin confirmation is text-based. “He is asked the phone number he wants to transfer the money to, the amount he wishes to transfer and then gets a call back from the bank to confirm the transaction.”

Bhashini has also collaborated with the Reserve Bank Innovation Hub (RBIH) to launch a Public Tech Platform for Frictionless Credit. This system supports multiple languages, making credit delivery smoother.

“Earlier, farmers would have to translate land records and hand them over to the banks to get their loans sanctioned,” said Nag. Now, the records are pulled from state databases, transliterated, and passed to banks. According to Nag, what earlier took two to three months now takes a day.

The future of voice-first banking

Bank outreach programmes are also evolving with AI-powered IVRS (Interactive Voice Response Systems), which can now recognise and respond in a customer’s regional language.

Before India’s economic liberalisation in the 1990s, banks communicated mainly in English and Hindi. As financial inclusion policies emerged, banks began using regional languages—but basic literacy was still required to understand forms and products.

In 2006, the RBI launched the Business Correspondent (BC) model to extend services to areas without brick and mortar branches. BCs helped non-literate customers access banking at their doorstep.

The Covid-19 pandemic further accelerated digital banking adoption. Over time, platforms incorporated regional language options. IVRS systems promoted banking products—but were mostly one-way and limited to touch responses.

“In rural areas, voice is a very powerful medium,” said Aditya Sethi, chief product officer at Awaaz.De, which helps financial institutions communicate with underserved users. “Rural audiences prefer speaking in their local languages than navigating English digital interfaces – whether they’re farmers or small business owners.”

IVRS had limits—it couldn’t truly listen. That changed with AI.

Now, users can interact with multilingual voice AI agents tailored to specific tasks: reactivating dormant accounts, qualifying leads, or automating renewals.

“In microfinance, field staff are primarily male due to long work hours and intense travel,” said Sethi, adding that clients, however, are mostly female in self-help groups. “Female voiced-based AI agents, designed to be empathetic, patient, personalised, and responsive, provide a sense of comfort and familiarity to women clients.”

The holy grail – full-fledged voice banking – isn’t far off.

Navana.ai has partnered with Bajaj Finserv, where its bot speaks six languages and closes Rs 150 crore in personal loans monthly.

“Voice-based banking services will be highly personalised to the user in terms of both their history with the business and interaction in their regional language,” said Nanavati. Navana.ai’s speech recognition model, Bodhi, is built for real-time use cases.

Bhashini’s CEO Amitabh Nag said testing remains the biggest hurdle.

“When you are doing partnerships with banking organisations, you need to do more testing in general because it impacts financial transactions,” he said. “That’s why adoption is taking longer.”

But large banks are taking notice. HDFC’s Gautam Anand, SVP and Head of Mobile & Net Banking, said that wearables and voice will change the way banking is conducted.

In an interview with Fintech News Network in March 2024, Anand noted that many in small towns and villages struggle with typing.

“The moment we enable voice in our mobile app, it will transform the whole thing,” he said. “For you to make an electricity bill payment or mobile recharge, you just have to speak into your phone.”

While voice tech may not fully replace traditional banking, industry leaders agree: it’s breaking new ground.

And for India’s low-literate customers, that could finally mean having a voice in the banking system.

Udit Hinduja is a graduate from the inaugural batch of ThePrint School of Journalism.

(Edited by Prashant)