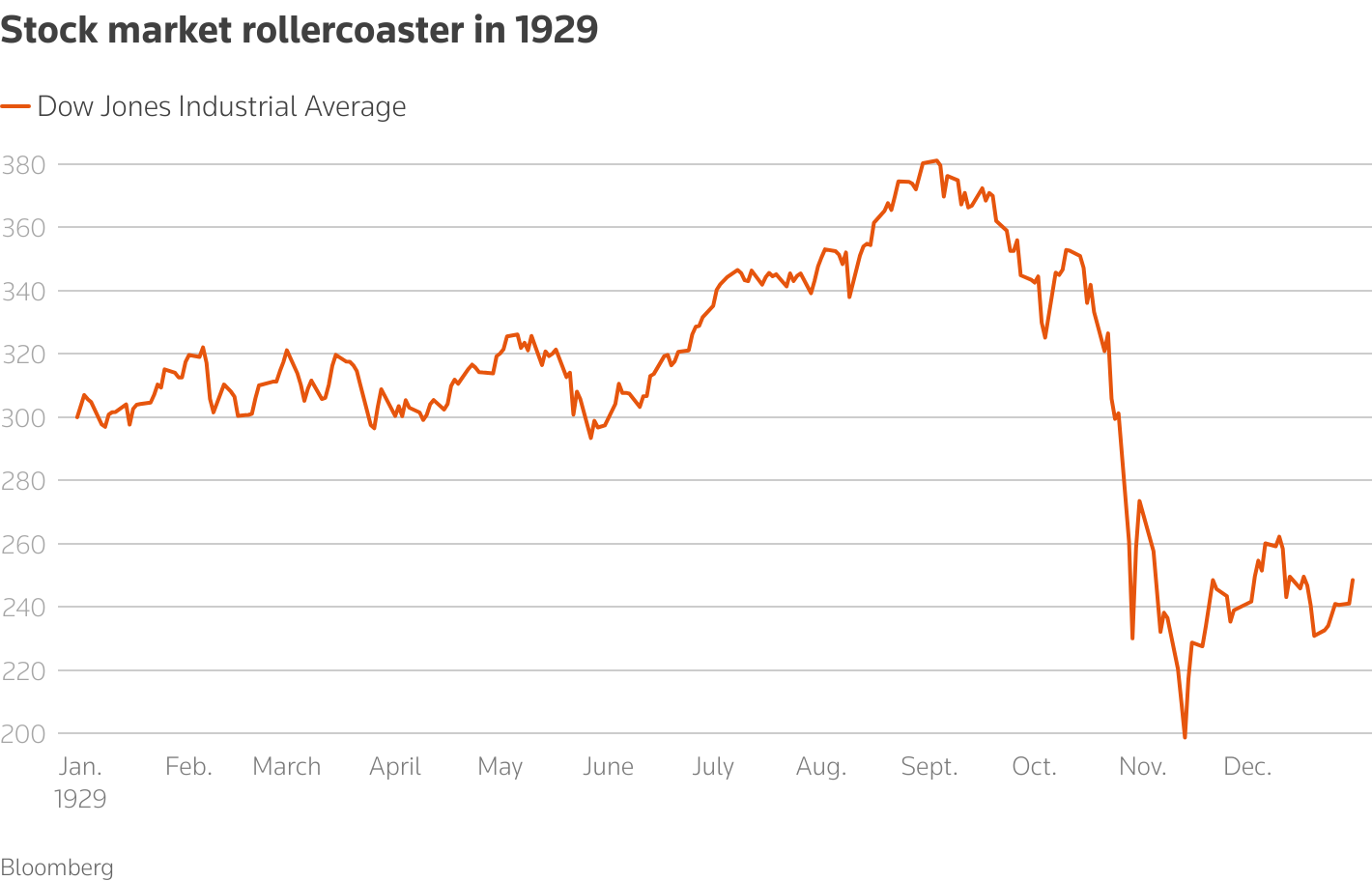

A short economic history lesson, however, highlights the tenuous link between crashes and contractions – and the challenge of determining what a depression even is.

Sign up here.

Yet, according to the article, it was the 1929 crash that scuttled Duncan’s dream of becoming a country doctor – a statement of cause and effect reflecting the popular belief that the Depression was a direct result of the crash.

In reality, however, the recession that metastasized into the Depression began in the month before the 1929 crash, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the official U.S. body that determines business cycles.

Economists differ on the reasons why the ordinary downturn that began in September 1929 worsened into the decade-plus-long Depression. Keynesians blame insufficiency of both private-sector demand and fiscal spending. Monetarists point the finger at a reduction in money supply that reduced credit, leading to a banking crisis and widespread bankruptcies. The 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff is also regarded as a contributor.

Absent from this debate is any suggestion that the economic slump either began with or was greatly intensified by the October 1929 stock market selloff. Yet that idea persists in the popular imagination.

WHAT EXACTLY IS A ‘DEPRESSSION’?

Not only are many people misinformed about when the Depression began, but experts also disagree on when it ended. The History channel says the Depression was over by 1939, while the Federal Reserve maintains that it continued into 1941.

The NBER considers a variety of economic indicators when dating the beginnings and ends of economic contractions, but the one most associated with the Depression in the popular mind is the unemployment rate.

It peaked at 24.9% in 1933, according to Statista. As late as 1940, however, it remained elevated at 14.6%, which is higher than the peak level of 11.7% recorded in the preceding recession from 1920-1921. It’s safe to assume that Americans facing an unemployment rate near 15% still considered themselves in an economic downturn, regardless of the label.

The lack of unanimity regarding the beginning and end of the Depression is understandable, given the vagueness surrounding the term “depression”.

In most countries, a recession is defined as two or more consecutive quarterly declines in gross domestic product. In the U.S., a recession is only officially a recession when the NBER says so. But “depression” has no precise definition. It is just, essentially, a downturn that is longer and more severe than a recession.

In fact, if we date the Depression from September 1929 to December 1939, then the U.S. economy was actually in contraction in a minority (45%) of the Depression’s 124 months by the NBER’s count. The full interval includes two separate NBER-designated recessions, from September 1929 to March 1933 and from June 1937 to June 1938.

LESSONS OF CRASHES AND RECESSIONS PAST

What can investors in April 2025 learn from this brief excursion into financial history? Perhaps the most important takeaway is that the link between stock market crashes and economic decline is not as tight as commonly supposed.

Consider that the decline the Dow suffered in 1929 as a whole, 17%, is the same percentage decline experienced in 1977 and 2002. If a 17% decline were sufficient to precipitate a recession, the effect was remarkably delayed in those later cases. According to the NBER, the next recessions in those two instances began in February 1981 and January 2008, respectively.

As it happens, 17% is also the magnitude of the Dow’s decline from its 365-day high on December 4, 2024 to its recent low on April 8, 2025.

But the market certainly does not seem to believe that a selloff on that scale guarantees that a recession is imminent. The median estimated probability of recession within the next 12 months among forecasters surveyed by Bloomberg is currently just 30%.

So why does being able to properly assess cause and effect here matter?

First, stock market declines, even steep ones, occur much more frequently than recessions, so it’s unwise for businesses or individuals to retrench every time the Dow suffers a serious decline.

A more reliable recession guide is the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index. When the six-month moving average of month-over-month changes turns negative, recession risk is especially high. Another red flag is a prolonged period in which U.S. Treasury yields on two-year maturities are higher than those on 10-year maturities.

Next, if the false causal relationship between crash and contraction makes individuals overreact to stock price declines in their personal financial decisions, this, at scale, could actually weigh on the real economy.

Finally, if a given recession is actually attributable to a fiscal or monetary policy error – including, say, a questionable tariff policy – wrongly blaming it on Wall Street reduces public pressure to avoid a similar mistake in the future.

(The views expressed here are those of Marty Fridson, the founder of FridsonVision High Yield Strategy. He is a past governor of the CFA Institute, consultant to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, and Special Assistant to the Director for Deferred Compensation, Office of Management and the Budget, The City of New York)

Writing by Marty Fridson; Editing by Anna Szymanski and Susan Fenton

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.